Work of all of these artists conveys a sort of shock factor, and by comparing each of the artist’s choice of media and content this text will explore how these work shock in different ways. Throughout Wilke’s life, her artwork explored the female body and the politics behind sexuality and power using photography. When Wilke was diagnosed with cancer, she continued to use photography as her main communication channel with the audience, with her images showing the drastic alterations her body went through.

Impacts of the disease are notably shown in ‘Intra-Venus,’ 1992-1993. The following text will explore how being diagnosed with cancer affected Wilke’s art by comparing her work before and after the diagnosis. Wilke chose to publically display an illness which many would prefer to keep private, showing the deterioration of her body by documenting the process of living with cancer to the viewer in a visually graphic way.

Many would question the necessity of showing such a private process in public, wondering why Wilke has chosen to expose such a personal part of her life to complete strangers. This argument will explore how and why an artist would choose to publicly display their illness, offering up their life to the audience’s scrutiny. Wilke’s work is very explicit. One can’t help but wonder: does Wilke want to shock the audience into somewhat going through what she is going through? Surely however her work is a constant reminder of this, so how then is it beneficial to Wilke to connect with the audience through shock? And how can the audience benefit from being reminded that this disease is present?

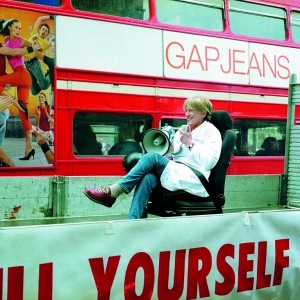

Baker similarly uses her illness as the subject for her artwork. However, instead of a physical illness, Baker suffers from a mental illness. Like Wilke, she is very direct about her personal life and how the illness affects her. Baker uses performance art as a way to communicate with the audience, with many of her performances being humorous as she mocks the British mental health system. This is seen in the 2000 ‘Pull yourself together,’ where Baker presents us with an autobiographical account of her experiences with the system, and her time living in mental institutes. This is deemed shocking as it is not politically correct. Like Wilke, this is all a first-hand account of how the artist has lived with their illness, and chosen to publicly express it. I will further discuss why they have chosen to do this.

As well as her performance work, Baker also uses her diary drawings to illustrate her emotions while living in the institutes, and at being diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. I will examine how the drawings and her performance art communicate the effects of the illness, and if the media used affects Baker’s ability to portray her emotions.

Like Baker, Darger’s artwork involves drawings that illustrate his thought processes. Darger’s unsettling pieces show the reality of a life in isolation, and how the human mind copes with this by creating another world to live within. It is this truth of his life that shocks the viewer. In contrast to Wilke and Baker’s publicly displayed artwork, Darger’s work was largely private until discovered after his death. This is particularly important in further examining whether it is important for the artist to communicate so publicly about their lives, and what it means for their practice. In doing so, I will focus on a sole piece of work by Darger: “The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion”,’ a fascinating story that illustrates his fantasy world.

The American artist Hannah Wilke was diagnosed with Lymphoma in 1987 and created work right up to her death in 1993. Lymphoma is a cancer in the lymphatic cells of the immune system which commonly presents as a solid tumor that can be treated with chemotherapy, and in some cases radiotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Wilke has experimented with materials such as clay, latex, chewing gum, chocolate and lint throughout her career, using her own boy in most of her work. The content of Wilke’s work often included tough truths about female sexuality, and the relationship between male and female sexualities. She also focused on the relationship between mother and daughter, and ageing and illness. Her work didn’t adapt when she was diagnosed with cancer, remaining true to her original idea of what she wanted the audience to see through her art work. Susan Sontag wrote in ‘Illness as Metaphor’ that “illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship.” Illness adds another layer of ‘otherness’ to the outsider status of womanhood. Wilke’s work after her diagnosis is a representation of the decaying woman, parodying her younger self and confronting her public with an illness which is felt in modern society to be “obscene – in the original meaning of the word: abominable, repugnant to the sentences.”

A running theme throughout Wilke’s work is using the female genitalia to convey the pleasure and pain of the female form to the audience. She represented female genitalia using ceramics, latex and chewing gum, often placing them onto the surface of her naked body for all to see. These vaginal forms became an important part of feminist art, aiming to portray the female body in a positive way. However, some critics, including noted feminist art critic Lucy Lippard have often stated that Wilke’s art was aimed for males, and even considered to be pornographic. Lydia Nead has noted that “a woman using her own face and body has a right to do what she will with them, but it is a subtle abyss that separates men’s use of women for sexual titillation from women’s use of women to expose that insult.” Wilke responded to critics who accused her of flaunting her body to appease a male audience by proclaiming; “People give me this bullshit of ‘what would you have done if you weren’t so gorgeous?’ What difference does it make? Gorgeous people die, as do the stereotypical ugly. Everybody dies.”

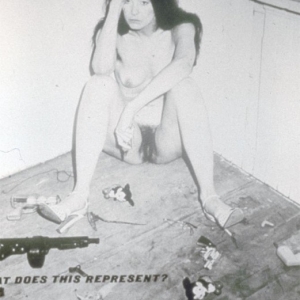

Photographs of Wilke’s naked self in what would be considered a ‘pin up’ style have regularly been branded egotistic and exhibitionist. What many of her critics failed to grasp was the tension she wanted to create. This tension is particularly evident through the contradictions present within the naked self-portrait photograph ‘What does this represent? What do you represent?’ In this image Wilke sits in the corner of the room with her legs spread open and surrounded by Mickey Mouse dolls and guns, signifying the frightening but also entertaining nature of contemporary social icons. Her look is blank, a frozen sadness that contradicts the natural temptation to turn the image into an erotic one. With the title of the piece at the bottom of the photograph, she challenges the viewer to question themselves and consider themselves in relation to the symbolism of the piece. The piece is also a direct reference to her eight year relationship with Claes Oldenburg, her ex-boyfriend and fellow artist. The relationship ended badly, and Wilke directs her pain and revenge on Oldenburg by addressing him directly as she asks: “What do you represent?” The objects surrounding her are references to his endless production of ray guns in the sixties and Mickey Mouse heads in the seventies. The objects are also strong symbols: the gun symbolises power and war, presenting the phallus as a throw-away toy and thus transforming it into a joke. Here Wilke is again communicating the difference between the sexes and interrogating the power between them by posing with these symbols. The audience then interprets the underlying meaning of these symbols and their position for themselves with the aid of Wilke’s visual imagery. Critic Debra Wacks wrote, “As I watched viewer’s reactions to Wilkes work/body, an elderly Danish man pointed to the photographs and said that he saw Wilke as a symbol of sexiness and as an individual woman. A woman with particular feminist ideas conveyed through warmth and humour. He added that he appreciated Wilkes technique because he recognized the power of the manipulated images.”

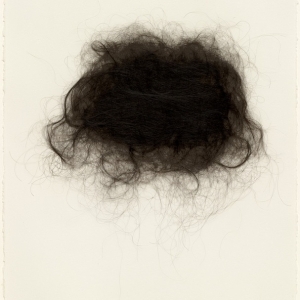

During Wilke’s treatment, she created a series of eighteen images called ‘Brushstrokes 1992,’ which were drawings made from her own hair as it fell out during her chemotherapy treatment. Attached to paper with invisible and fragile adhesive, the hair forms different shapes, some delicate and some bold. As put best by Wilke’s husband Donald Goddard, the drawings are “like distant, infinite nebulae and the inevitable, random movements of life, all at once.” These ‘brushstrokes’ reveal an unsettling relationship about morality and loss, compounded by the fact that in Victorian times, hair from deceased loved ones or first hair cuttings from a baby were kept in lockets or woven into jewelry. This work seems more personal and introverted compared to her other pieces: there is no image of her, just the hair on the paper. These were exhibited separately from the other work in the June 2010 “Hannah Wilke: Elective Affinities” at the Alison Jacques Gallery in London, which suggests that Wilke wanted the work to be hidden away, and maybe even missed by the viewer.

‘Intra-Venus’ was Hannah Wilke’s last work before she died. She started making the work in 1991, recording the development of her illness and the progressive decay of her body using a series of photographs which documented the reality of her physical and mental deterioration. The photographs are similar to the ones she took of her mother, ‘Portrait of the Artist with Her Mother, Selma Butter,’ which shows her mother’s own struggle with cancer. The photographs that shadow the ‘Intra-Venus’ series document the decline of both her own and her mother’s bodies, suggesting that Wilke wanted us to see how the body is able to deteriorate so quickly, and how vulnerable one can become. The side-by-side photographs show the youthful woman looking into the mirror to see her older self-reflecting back, locked in a state of physical decay. Her mother’s gaze is understandably averted from the camera as we see distressing scars from her major surgery. In contradiction to her Mother, Wilke is staring straight at the camera in a provocative, almost arrogant way. She is a picture of health, accentuated by baby blue eye shadow and pink blush, with the smooth skins of her breasts in direct opposition to her mothers. Wilke’s partner spoke about how the project affected her and her mother’s ability to communicate the experiences of the illness and love and loss: “doing the work was extremely important to Hannah. Her mother, Selma, was a wonderful woman. They loved each other and it was very apparent. Hannah took a lot of pictures, and says it was a way of keeping her mother alive. She hoped that it would literally do that. Of course it didn’t.”

Vulnerability is an important part of Wilke’s work. She created objects made from unusual materials such as thin clay, paper and wax, and placed these objects in strange places: pinned or glued to the walls, or simply left on the floor. The objects seemed on the verge of disaster, making the audience anxious as they questioned whether they would fall off the wall, or crack and be destroyed. In 1975 Wilke said that she “struggled with the idea of her work disintegrating, because it’s hard to admit that you’re going to die yourself. I’m not denying the fact that I’m going to go, yet it still hurts to see some of my early work go before I do.” This shows that by producing art work about the cancer, Wilke is able to remain alive through her art long after she has died. Her art works becomes evidence of her existence.

Most of the photographs in the ‘Intra-Venus’ series are of Wilke in bed, whether a hospital bed or her own. Whether you are sick or healthy, bed is a significantly symbolic part of our identity. We are generally born, sleep, and make love on a bed, and we die there. The fact Wilke has been photographed in this context provides us with a much more personal account of her life. In contrast to previous photographs that show Wilke in Playboy style poses, she now appears in bed, struggling with her illness. A lot of the photographs in the series are unnerving and hard to look at, as they convey such a generally taboo subject in its extreme. In “Intra Venus series no.5,” (Fig.5) Wilke appears in a nightgown in the left photograph against a grey background, looking tired and sore. Her eyes are blank; her chest is blotched with broken blood vessels, and she has tubes taped to her body. The most horrific part of the photograph is her tongue, which is partially skinned due to the chemotherapy. The photo on the right challenges the left, with Wilke’s refusal to invite pity shown through her brightly coloured t-shirt and the turban like cloth wrapped around her head, coupled with her outraged expression: her bright red tongue sticks way out of her mouth, whilst her eyes are squeezed shut. The difference between this and her previous work is massive, but the content and the humour is still present- maybe not in her poses, heels or raised eyebrows, but within her ability to mock the illness and her situation. Although Wilke is obviously going through a horrendous time, she still strives to communicate her experiences as honestly as she can with the audience. What Wilke experienced is real, and her work appears as a documentation of her horrific journey. We can see the changes not only in her body, but also in her face. In her earlier photographs, even in works created just after she was diagnosed, she is smiling: still positive about her ideas and her aims for her art. However, as the cancer gets stronger, you can see her face become paler and withdrawn; the spark in her eyes disappearing. Wilke is no longer smiling, but just existing. It is important that she kept documenting this process even though it is hard for the viewer to watch her decline in health, both mentally and physically.