In 2002 the British Library held a book illustration exhibition, and in the exhibition’s accompanying book, Magic Pencil, Joanna Carey wrote, ‘Book illustrations don’t often find themselves in galleries, framed and submitted to the public gaze as independent art objects’.

Since 2002, however, I have been to a number of different exhibitions featuring book illustrations. Some are aimed at selling the original drawings, paintings and prints, but most exhibit the illustration as artwork to be viewed and admired.

Many successful book illustrators are famed for their contribution to children’s books. Whilst adults respond objectively or emotionally to pictures and images, children’s reactions are sensory too.

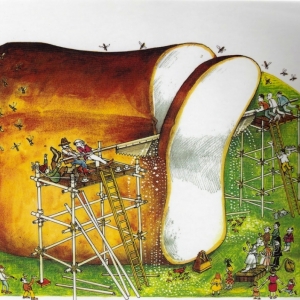

When my brother recently gave me a copy of a former favourite book from my childhood, The Giant Jam Sandwich, I somehow ‘felt’ the pictures when I looked at them. The texture of the jam, the sharpness of the wasps, and the animated facial features of the people were things that I would not have felt as vividly had I seen the book for the first time as an adult.

The reason we love children’s book illustration is undoubtedly connected with personal memories from one’s own childhood but adults also appreciate the talent of the artists, and are able to marvel at the artistic merits of the illustrations.

Like so many others, I greatly admire the work of Quentin Blake. Using sketchy, rapid lines, the people and animals he draws are credible, real, and wonderful representations of the characters in the story.

The viewer instantly feels uplifted by the lively movement and humour conveyed by his pictures, and even though the subject matter is sometimes dark, the viewer is compelled to respond positively.

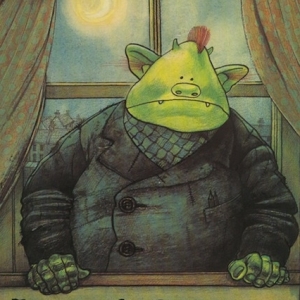

Raymond Briggs is similarly talented at making the gritty seem palatable and entertaining. Fungus the Bogeyman was really quite disgusting as far as subject matter is concerned, and he revelled in it, using repellent yet enticing colours and textures

The viewer is also captivated by the meticulous details in his pictures, and as a child I found them utterly compelling.

The appeal of pictures by Blake and Briggs, and others such as Posy Simmonds, lies in their intelligence and humour. There are other children’s book illustrators, however, whose work appeals because of the overall atmosphere they produce.

The British Library compilation, The Magic Pencil shows two different illustrations by Emma Chichester Clark. One is a haunting, ambiguous scene taken from It Was You, Blue Kangaroo! depicting a toy kangaroo jumping down from a bookcase.

The image is made more eerie by the use of dark colour, adding a claustrophobic feel to the image.

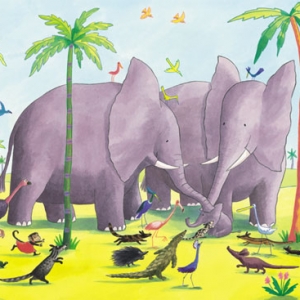

In contrast, the other scene, from No More Kissing! is warm and inviting, using bright colours with predominant yellow and rosy hues. In this picture there is no eeriness or tension.

Instead, a sentimental, harmonious scenario depicting elephants, monkeys and other jungle animals in happy circumstances. The former image is enticing because it evokes our curiosity, whereas the latter is attractive and pleasant to look at.

It goes without saying that art often expresses and reflects contemporary social and political trends, and has even provoked social and political change. Perhaps illustrations from children’s books are seen as passive in comparison, which may be why it took so long for them to be credited as artworks in their own right.

However, children’s illustrations have made, and continue to make, a huge impact on the way peoples’ brains are essentially ‘wired’. Whenever I hear the words ‘fat cat’ for example, I automatically think of a haunting image of a fat cat from a book Mrs O’Grady’s Garden which I had as a child, and which I have not seen for over twenty five years.

The images in books I had as a child have left an indelible mark on my memory, and while they may not have influenced my character or actions, in subtle terms they have formed many of the unconscious mental connections I make in every day life.

There are various children’s books where any one page could feature as an artwork to be exhibited on the wall of a gallery. A page in isolation may not be self-contained in terms of its narrative and meaning but the same could be said for many modern artworks that feature in gallery exhibitions.

It makes perfect sense that children’s book illustrations should be worthy of being exhibited, not as inconsequential ‘pretty pictures’ but as intelligent pieces, which may have been produced for our entertainment and have ended up becoming part of our psyche.