As allegories go, Botticelli’s Venus and Mars is possibly the most controversial.

Venus, the voluptuous goddess of love, pleasure and fertility left her husband, a modest but divine blacksmith, for the virulent God of War, Mars. Together the illicit couple had many children; the most Venus ever bore with one individual.

These ideas are not as old fashioned as we might imagine. All contemporary wars are justified to the public through some elaborate, skewed or misapprehended version of the above.

But sometimes, when we are lucky, artists appear when we are being lied to, and they try to reveal the truth. Whether we listen or not, is an entirely different matter.

A perfect example of this the art that accompanied a terrible conflict, the Second World War. The art movements that arose from the feeling of dread, unease and impending doom are the most hopeful things that ever came out of something so devastating and destructive to our sense of humanity and community.

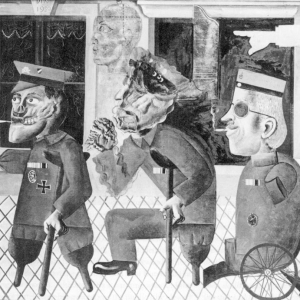

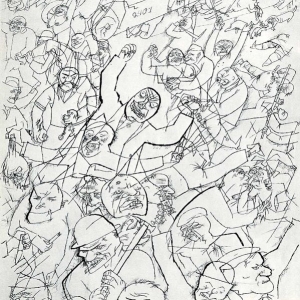

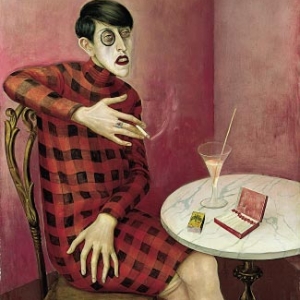

Although at first glance they do not seem hopeful in the least, the jeering jests of Otto Dix and George Grosz in their all singing, all dancing representations of German ‘degenerates’; or as we might see them, champagne swilling, cabaret dancing, young people trying to escape the lasting legacy of WWI.

Whilst simultaneously casting a spot light on those who would steal our freedom and force us to violently and abruptly confront the capabilities of our power to eradicate all that we have created, such as lawyers, politicians, and the worst offenders of all, members of the priesthood.

These caricatures are not pretty, or examples of flawless technique, or anything like Botticelli’s allegory that provides us with a very gentle thinking point about the nature of love and war.

What the caricatures are, is very clever, very insightful and most importantly of all, they are very honest. Above all, however, they are a contradiction in themselves, an offensive gesture up at Hitler’s own neo-classicistic, plastic- romantic, faux- sentimental taste in art that he inflicted on everyone.

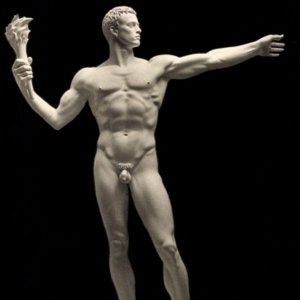

Furthermore, Nazi approved art, particularly the nude sculptures of Arno Breker, both in their powerful, impenetrable physique and their severe, resolved expressions, encapsulated a contemptuous regard for the weaker nations that Hitler’s army would come to conquer.

The nude as a fascist ideal created the illusion of infallible strength; and this proved to be an indispensable means of propaganda, empowering the National Socialist Party’s supporters whilst intimidating its opposition.

The works of artists from movements such as Dada and New Objectivity were ugly for a reason. They forced their audience to look at themselves, and to be ashamed of what they saw there.

Paul Delvaux’s painting Sleeping Venus, 1944, appears to be an indictment of pre-war ideologies, now rendered moot by the horrors of World War II.

The impending sense of loss of the ideals that were eradicated by the sheer volume of fatalities can be observed in Delvaux’s work through the symbols used, which are considerably regular fixtures in the Western Canon.

The Venus, a symbol of beauty and feminine sexuality, sleeps soundly, oblivious to the skeleton which looms above her, conversing with the Victorian lady in all her finery and moral upstanding.

There is also an architectural composition in the painting – a classical building, as well as writhing naked figures in the background, one of which appears to be beseeching the heavens for a salvation which does not come, possibly a testament to the collective fear and desperation felt in the face of the German bombs.

Now a permanent fixture in the Tate Modern, the caption which accompanies the work reads: ‘Delvaux later explained that it was painted in Brussels during the German wartime occupation and while the city was being bombed. ‘The psychology of that moment was very exceptional, full of drama and anguish’, Delvaux recalled.

‘I wanted to express this anguish in the picture, contrasted with the calm of the Venus’.’ This in many ways exposes the Venus as a shallow and vain figure, immune to the suffering of humankind, but her immortality can also suggest the perseverance of beauty and desire; a possible salvation in the face of destruction.

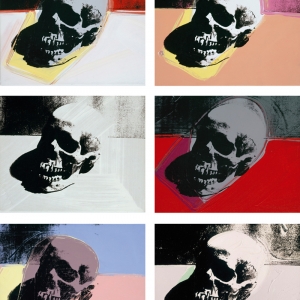

Warhol’s Death and Disaster works also acknowledged the capacity of the viewer to feel their mortality, regardless of social background and access to high art, they needed simply to open a newspaper to be reminded.

After Warhol was shot and critically injured by Valerie Solanas in 1968, his art focused on death even more than it had done so previously: ‘the skull, a traditional symbol of mortality, is repeated six times, with the impenetrable darkness of the hollow eye sockets echoed in each image.’

Warhol’s Skull series of the 1970s, in its use of bright colours of the flowers in contrast with the sobering motif of the skull, can be considered a post-modern rendering of the Vanitas; a single skull surrounded by the brilliant neon colours of Pop.

Post-war art then, reflected a similar disenfranchisement of the individual, and a mourning at the loss of so many souls not accepted entry into the systematic dystopian hell of fascist regimes.

Art of this period forced us to grasp a new mirror, which revealed ourselves as far too well acquainted with our own fragility, mortality and vanity. It also introduced us to a new culprit that weaved its way into our daily lives like a serpent and threatened to devour all; mass consumerism.