Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ initially presents a fascinating paradox to the modern viewer.

Despite its apparent simplicity, it is a highly complex work in composition and interpretation. It is rooted in both the time and place of its creation and yet, is timelessly transcendental, with elements that are both realistic, rational and mystical.

It is a testament to Piero’s ability that he was able to meld such disparate elements into a masterpiece of the quattrocento. The Baptism is firmly rooted in Renaissance humanism.

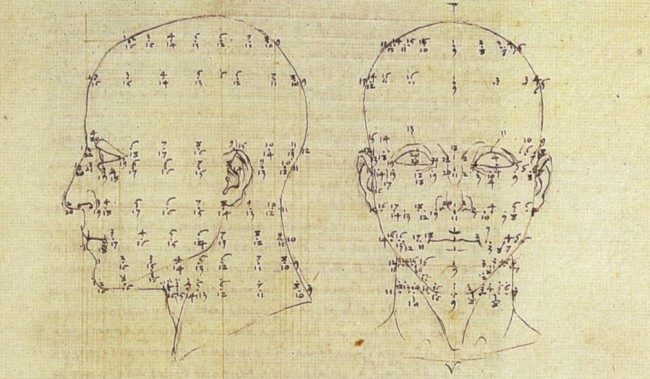

Hence the figures form the focus and are painted in a sculptural way that expresses their physical humanity. Not only are the individuals perfectly proportioned, but the overall scene also has a careful geometric order, creating a pleasing harmony and stability.

Christ’s figure is bisected by the central vertical, which runs through the dove, fingertips and right foot. Furthermore, the fingertips form the centre of both an equilateral triangle and pentagon, which symbolize the Trinity and Five Wounds respectively.

Piero masters linear perspective, positioning Christ and John some way behind the picture plane to draw the eye and also makes them life-sized in relation to the viewer, enhancing the realism.

He was known to his contemporaries as a great scientist, publishing works such as De prospectiva pingendi. Science was thus central to the realism of his work.

Beyond the composition and execution, Piero also ensured the setting was familiar to his contemporaries, placing the scene in the Tiber Valley, Tuscany just outside his hometown Borgo Sansepolcro, which can be seen in the background.

The Baptism, which now hangs in the National Gallery, has lost some of its original immediacy as the landscape is not local, yet Piero’s point is still clear: he was intent on rendering and arranging both the people and the scene to maximise their visual impact, using rational approaches to configuration and implementation.

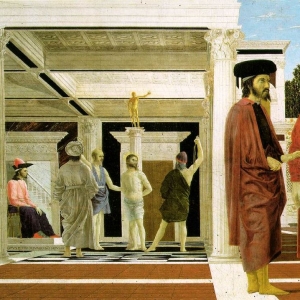

However the painting is much more than just a technically impressive piece. Its layers of allegory and symbolism create a spirituality and unreality, which seem initially at odds with its rational composition.

It commemorates Christ’s baptism, which is traditionally celebrated on the 6th January, together with the Adoration of the Magi and Wedding at Cana. The meaning of the work is therefore complex.

The group of angels on the left, not only follow an artistic tradition of angelic presence at the baptism, but also allude to matrimony through their gestures, interaction and dress. They appear somewhat bizarre and mystical to the modern eye, as does the group processing along the river in the mid-ground, dressed in colourful, Eastern-style clothing.

The latter represents the Magi and the artistic tradition of the presence of elders at the Baptism, as well as referencing a delegation from Constantinople.

The lone figure stripping off in between them and Christ is thought to be a catechumen preparing for immersion, intended to symbolize baptism as salvation and rebirth.

The walnut tree to Christ’s right, or noce in Italian, refers to the valley’s name, Val’ di Nocea, as well as to Psalm 1:3. Such scriptural and allegorical allusions also serve to bring a uniquely timeless quality to the painting, allowing us to see beyond its Renaissance humanism.

The beauty and accomplishment of the Baptism is reflected in how it combines so many diverse elements so effectively. To contemporary eyes, the contrast between a technique emphasising realism and logic and a subject, which appears so unreal and mystical, is initially puzzling.

However, when the Baptism was painted in c.1450 there was little distinction between religion and logic, indeed it was the technique rather than subject which would have been more challenging to contemporaries.

Artists like Piero brought classical and scientific approaches to Christian narratives. As theology was regarded as the “Queen of the Sciences” the science deployed in the painting serves only to enhance its spirituality.

This is exemplified by the river, which seems to stop before Christ and John’s feet, recalling the miracle of Joshua halting the River Jordan.

However it is also a trick of the eye: the point at which the river seems to stop is also the optical point at which water stops reflecting light although, in reality, it continues flowing.

Realism and spirituality therefore fuse in the painting to produce a remarkable tranquillity, clarity and sense of eternity, making the Baptism of Christ an incomparable achievement.