In his exhibition ‘Model and Metaphor’, Charlie Stiven uses photographs to alter the representation of highly detailed models, placing small scale sculptures in situations which, in photographs, appear real.

We as viewer see the models in their original guise. Small, intricate pieces which could conceivably be based on real buildings.

And yet we also see the photographs which attempt to locate the model in a believable setting, with generic scale backgrounds housing the structures. His use of the camera aims to “create a slow ’double take’ response”1, manipulating the perception of the viewer, whilst gently ensuring they realise their forced lull into his carefully crafted deception.

In About Looking, John Berger responds to Susan Sontag by exclaiming that the camera “surveys us like God, and it surveys for us.”2

He suggests, in a manner wrought around Sontag’s text, that photography has not simply been a technological means of capturing images, but has altered what the image is by altering the way we look at things.

In her On Photography, Sontag suggests that the camera is a means of “acquiring a sense of reality”, and we can see how Stiven uses the camera to enforce a different reality on to the perception of the viewer.

This exhibition also conveys, in large part thanks to its positioning in central Belgrade’s Graficki Kolektiv, something of the fear that Sontag talks of when she exclaims that “an image world is replacing the real one.”

Stiven consciously plays with this blurred distinction of the image and reality. He admits, in the exhibition catalogue, that his architectural models are fictitious “props”3 in a space in which the viewer feels very much the viewed; where the displayed photographs survey us and survey for us.

That Stiven admits to his attempted deception is crucial to understanding his work. His affect is only made possible by his use of the photograph.

He would be unable to fool the viewer of the copied reality of his sculptures if he did not place them within the constructed space of the photograph.

This perhaps agrees with Sontag’s idea of the image world replacing the real one, as the viewer can only be duped by believing that what they see in the photograph is a representation of reality.

By being the vehicle for Stiven’s intention, the photograph essentially ‘surveys’ the viewer, as they ‘survey’ it.

However, the layout of the exhibition, in its imposing home, threatens to undermine this core intention through overcrowding.

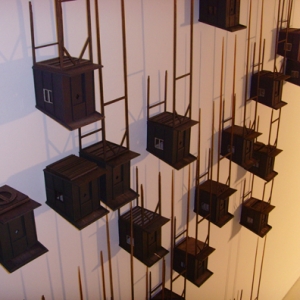

‘Model and Metaphor’ is a mixture of sculpture and photography displayed on the wood-panelled walls and clinical glass cabinets of the Graficki Kolektiv. The ‘Model’ side of things is represented by the sculptures; small, seemingly scale versions of real buildings.

They are meticulously designed, each individually detailed and carefully unique. And yet we find, on some of the walls of the exhibition, that certain structural dimensions are repeated, with multiple creative attempts at a similar prototype.

These are Stiven’s upside-down watchtowers, remnants of his exhibition ‘The High Ground’, in which “different combinations of architectural detail” are “employed to emphasise the fact that what is most important, of most value, is not which is on the surface…but that which lies beneath.”4

There is too little space within the GK to simultaneously house multiple exhibitions and I found myself confused as to which work related to which. A reviewer of ‘The High Ground’ suggests that the first instance of its exhibition also suffered due to its location within the gallery.

This installation was “found at the bottom of some rather foreboding steps that more resemble the route to the toilets than the entrance to an exhibition space.”5 We hear mentions of Stiven’s press release for this exhibition too (also included in the ‘Model and Metaphor’ catalogue), with the review struggling to find pointed examples of “’the absurdity of dogma’”6.

Stiven’s exhibition catalogue is, on the whole, plagued by these overly wordy suggestions of what his work achieves. Through the models and photographs under the moniker ‘Model and Metaphor’, we are invited to view a work that “is not about art…. but about life.”7

Stiven’s lofty intentions seem to be marred somewhat by the display of various strands of his work and thought.

The reviewer of ‘The High Ground’ finally comes to a rather puzzled conclusion as to whether the strange positioning of Stiven’s work was in fact “all part of the plan”8, but leaves an ominous question mark at the end of her review as if to ask, ‘what plan’? Both myself and Ms Owen come up against the obstructions of too many words and too little space.

The work is compelling, the models expertly detailed and the discord between the image of the photograph and the fabricated wooden constructions is – for a short while – cunning.

Yet stepping out of the gallery, and then back inside, one comes to realise that the gallery space, and its surroundings, contribute more to the feeling one gleans from the exhibition than the work itself. But it is never made entirely clear that this was Stiven’s intention.

The interior of the GK conveys a sense of mythical secrecy. The divide between the lower opaque section of the gallery and its permeable windowed top is punctuated by the presence of a silent office space above the displayed work.

The walls form the shape of a Greek cross, ensuring that parts of the exhibition are sometimes hidden, sometimes revealed, depending on the position of the viewer. The space is tight, and almost enhances the sense that the viewer is being watched, with its glass entrance doors and the aforementioned ‘watchtower’ of the office above.

Passers-by can observe the internal observer, and other visitors can hide themselves around the multiple corners. During my time in Belgrade, I met and befriended the artist Mark Brogan, who is in residence at the BIGZ art space, further south along the river Sava. He suggests that until recently, the art scene in Belgrade “was very politicised, activistic and becoming far too ideologically biased”9. One can sense, within the GK, a certain aura of secrecy and surveillance, which perhaps communicates some of the traditionally Belgradian politicisation of art spaces.

In something of a departure from the more “temporary”10 feel of the neighbouring space of the Kulturni Centar, the structure which houses this exhibition feels strongly immovable, staunchly surviving the bombing and blasts of mid-to-late 20th century Belgrade life.

Minutes away, one can see the bombed remnants of the Yugoslav Ministry of Defence, leaning over one of Belgrade’s central arteries. There, the windows no longer exist and the NATO bombings of 1999 are opened out to scrutiny.

Here, at the GK, the viewer is both slightly isolated and protected from the street, but also constantly in line for scrutiny. The gallery does not afford a substantial dividing area between the street and the exhibition space, and so the work is made visible by an uneasy mixture of natural and artificial light.

The work inside the gallery is very much affected by the goings on of the very central, very historically charged Republike Square, and the internals and externals of Belgrade life still feel very much imposed upon by the government.

Without getting overly political, one can feel the rumblings of dissatisfaction amongst Belgradians, who are caught in a city lurching between being a shining modern example of cross-cultural integration, and yet stuck in the throes of a harsh government, who have recently brought about stricter laws on social meetings and out-of-hours drinking.

And this is still a city which, despite its lavish and bustling artistic and bohemian scene, also harbours Orthodox attitudes towards homosexuality, left-wing politics and other religious practices.

And so it is with some surprise that Stiven’s intention “to open up a contemplative resonance which has at its core a concern about aspects of the human condition and the social, political and economic consequences of these”11 is somewhat fulfilled. The viewer is not always afforded the space or clarity of vision to explore and question.

Much of his intended deception is as much a result of Stiven’s overwrought catalogue diction and the very idiosyncratic strangeness of the Graficki Kolektiv gallery space. Yet Stiven does succeed in deceiving his audience; the displayed photographs of his small architectural models, imposed into seemingly real situations, do cause surprise.

The internal make up of the space of the Graficki Kolektiv tends to overwhelm and confuse the exhibition, imposing itself on the work.

Its claustrophobic simultaneity of an imposing interior and intrusive outside bustle ensures we are not given the space to ponder each section of Stiven’s work, nor able to explore the intellectual depths into which we are invited. And yet, we recall Ms Owen’s review and ask, tentatively, if this was all part of Stiven’s plan?

For because of the gallery and its location within Belgrade, we feel that not only do Stiven’s models indeed act as “props”, delivering something of a “contemplative resonance”12 to the viewer, but also the viewer comes to perceive themselves as a prop, as part of a performance in which the process of realisation is swift, but the lasting sense of manipulation lingers.

Recalling Berger and Sontag, the image world of Stiven’s photographs interacts neatly with the fabricated ‘image world’ of the gallery space – the harsh double-take response intended by Stiven does actually happen.

And also the viewer finds themselves both the surveyor and the surveyed, both in relation to Stiven’s photographic constructs, as well as within the isolated but easy-to-survey Graficki Kolektiv.

The viewer finds themselves at the crossed-centre of various interactions – surveyed, surveying and borne down upon by Stiven’s intention, the confines of the gallery, and the intense political environment of this East-European frontier.

1 Charlie Stiven, Catalogue for ‘Model & Metaphor’, Graficki Kolektiv, Belgrade, Summer 2013, p. 2.

2 John Berger, ‘Uses of Photography’, in About Looking (London: Bloomsbury, 2009), p. 59.use

3 Stiven, p. 2.

4 Stiven, p. 6.

5 Jennifer Owen, ‘Charlie Stiven: The High Ground’, The Journal, 22nd February 2010

6 Owen, para. 4.

7 Stiven, p. 2.

8 Owen, para. 5.

9 Mark Gerard Brogan, via email, 23/09/2013.

10 Mark Gerard Brogan, via email, 23/09/2013.

11 Stiven, p. 2.

12 Stiven, p. 2.