I have neither the time nor the expertise to be able to add anything to the debate regarding the authenticity of Christ Risen (c. 1511), a newly rediscovered painting attributed to Titian. Apparently, paintings by this Venetian master are like buses; you wait ages for one and then two show up at once – the National Gallery has also recently reattributed a work to this most marketable of artists. Lets assume for a moment that it isn’t by Titian. In fact, let’s pretend that instead of being a rediscovered painting, this is an entirely new artwork. With this in mind, is it worthwhile considering whether or not this is a good painting?

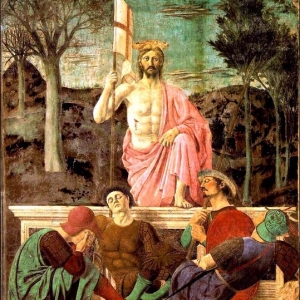

We are confronted by Christ resurrected. We know this because he bears the scars of execution, holds the traditional banner of St George, wears a shroud and stands atop a tomb. The artist also cleverly hints at the act of resurrection through a suggested sunrise in the background. This is literally, and metaphorically, a new dawn.

The painting avoids superfluous detail; the resulting clarity serves to communicate a message. That message is the divinity of Christ, the omnipotence of Christianity and eternal hope for mere mortal sinners. Serious stuff indeed.

Religion aside, the painting is also subjectively beautiful. The composition is roughly divided diagonally. Cool tones, shadows and thick foliage to the top left transition to warm hues and an absence of matter, punctuated only by the delicate flagstaff and mid-ground shrubs, to the bottom right. This is delicately balanced by the figure of Christ, which serves to focus the viewer’s attention.

Such confidence and bravura are the hallmarks of uncommon skill. However, the maker only partially achieves the illusion of 3D space. Although the proportions appear accurate – deft touches such as Christ’s foreshortened left foot help to reassure the viewer – the front-on perspective undermines the solidity of the tomb, which appears to exist on an entirely separate plane to the background scenery. This is perhaps because we are supposed to view the painting from below, or that portions of the work may be missing. The figure of Christ also appears to be lit from above and slightly to the left, despite the fact that the only visible light source is located behind and below the figure. This can likewise be explained by the presence of an unseen ‘divine’ light, or perhaps indicates a real-life light source in the original location.

Resurrections are typically triumphant and masculine. Piero della Francesca’s Christ at Sansepolcro, for example, looks more like a zombie out for revenge than a man who turns the other cheek. This Christ, however, only partly conforms to the tradition. There is a fleshy, perhaps even feminine, softness to the figure. Thus Christ is altogether more human, sexualised and indeed vulnerable. This serves to temper the bravado and reminds the viewer that Christ was supposed to be flesh and blood. The scene is depicted as a literal resurrection, not a divine apparition.

Whilst Titan’s painting embraces sensuality, it rather lacks drama. Strictly speaking, Christ Risen is not a Resurrection. And here in lies my only real gripe. Paintings that depict the process of resurrection, literally, one foot still in the grave, have more dynamism, movement and suspense than our ‘new’ Titian.

Old masters often get a free pass from art critics. The passage of time and collective pedestalling seems to erode objective judgement. And yet, setting aside provenance, monetary value and canonical significance, it is always worthwhile considering artworks from an aesthetically critical point of view.

So is this the real thing? Frankly, aside from those with a financial stake in the painting, who really cares? This is good art.