Schendel uses literary influences to both guide the structure and themes of her work. This creates a playful interaction between words and images, function and form, sound and silence, and art and life itself. In this way, the artist inquires into the very fabric and seams of human life and explores philosophical questions of being, believing and voids. This focus is reflected in the types of literature she draws upon, as it is mostly philosophical being by the British theologian John Henry Newman, and the philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein and Jean Gebser.

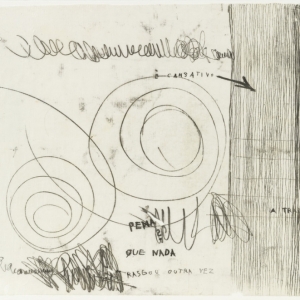

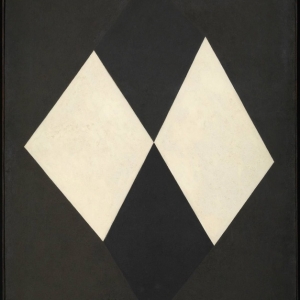

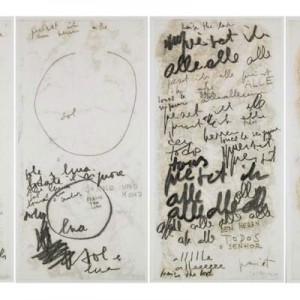

In Schendel’s work words often dissolve or fragment, suggesting that nothing is transparent and that there is no stable form of expression or meaning. This poses questions such as how can we adequately express and represent ourselves, and what really gives meaning and substance to our existence? The unstable and baffling nature of these questions positions Schendel’s work in a liminal space, occupying thresholds of uncertainty, mystery and intrigue. This allows the work to place itself on the edge of life and ‘readable’ signs – or even inbetween forms of expression – in a way that enables critique of the human existence. Indeed, the work plays with the notion of voids, of being and non-being (which is partly conveyed in the use of monochrome and recurring juxtaposition of black and white colours).

Despite the artist’s experiments with the dissolution of form, there is always a return to words in her work. The words are presented as beautiful, transient, playful, teasing, suggestive, and even threatening in their resistance to being ‘decoded’. It is as though the paintings create half-worlds, or ‘present’ voids, which are just out of our reach.

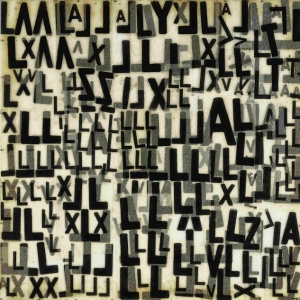

The use of abstraction places emphasis on form, allowing the words to take on a life of their own and become objects in their own right. This prevents absolute ‘readings’ on the part of the viewer, and instead gives way to an initially more aesthetic and ponderous engagement with the artwork. Certainly, Schendel’s art works on us over time so that impressions and ‘meanings’ are released slowly. In this way, aesthetics and philosophy are intertwined. Additionally, the objectification of words appears to question whether ideas are external or internal to our beings. Do words and systems of meaning exist without us? Do words convey their own lives and work to their own agendas?

By combining abstraction, which is removed from everyday experience, with words that are the most common method of communication, the artworks ask us to look again at how we construct our reality. Everything is put into question and defamiliarised. Due to this, the work presented in this exhibition prompts a fresh engagement with life and the philosophy it alludes to.

Schendel increasingly worked in series, which allowed her to further deconstruct or experiment with the forms of letters and words. This methodology also suggests her work is self-conscious and obsessive in its inquiry, and aims for perfection or answers to a problem. This serial work additionally points towards the artist’s use of multiplicity, in both form and theme, as she uses multiple vessels of human expression.

It is interesting to see her increasing involvement with abstraction of pure letters and form, and how this tips into profound meditation on philosophical questions when combined with installation. Even though the work is progressively abstract, the viewer and ‘reality’ is kept in mind through the nature of the philosophical questions as well as by the characteristics of installations, which require people to actively walk around them and notice forms from different angles.

Maybe due to an initial miscalculation of its popularity, this exhibition has been extended; a phenomenon the curators at the Tate cannot remember ever happening before.