The Saatchi Gallery’s latest exhibition, Body Language, interrogates ways the human body is depicted in international contemporary art.

The result is not, as some critics might have hoped, the sign of a renewed interest in purely figurative art.

Rather, the works exploit the concept of the human body as a platform to explore ideas of sex, violence, artifice and control.

As befits art representing people in an age when a snapshot can be diffused around the globe in a matter of seconds, many of the figures in this show seem wary of the viewer’s intentions, often with an evident desire for control over their own image.

The female figures especially are far removed from being the submissive subjects of modernist painting; instead self-aware women of the digital age.

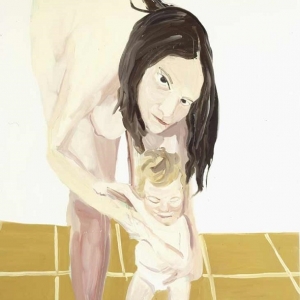

Chantal Joffe’s painting Mother and Child II (2005) features a nude mother looking out at the viewer suspiciously, hunched protectively over her baby. This is not a romantic scene of maternal love, but rather the depiction of a mother’s caution over her family’s loss of privacy.

In Black Camisole (2004), a painting based on a fashion magazine photo, Joffe uses a slightly exaggerated, foreshortened perspective to give the impression of a scantily-clad model backing away from the viewer’s gaze, her nose in the air, as if disgusted by the possibility of lustful advances.

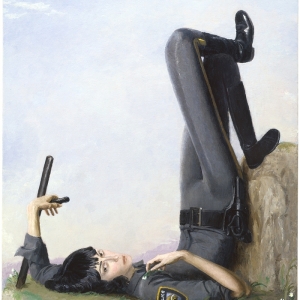

Jansson Stegner’s paintings also attack clichéd ideas of female submission; the sensually-posed women of his cutesy, pastoral scenes are in fact truncheon-wielding police officers.

The female officer of Sarabande (2006) holds a plucked daisy delicately in one hand and a truncheon in the other, a broad juxtaposition that plays with concepts of sexual passivity, fetishism and violence.

The ultimate woman-in-charge of the show is Michael Cline’s Woman in Doorway, O.K. (2007), who dominates the heightened reality of her painted surroundings. Standing naked on her doorstep with her legs spread, she calmly smokes and drinks a soda whilst an old man falls at her feet, and another is imprisoned in what seems to be her own private jail.

She is totally in control of the surreal, cartoonish composition and, as the painting’s title and the woman’s smoke rings suggest, this is all ‘O.K.’.

While some works show people taking control of their own bodies and environments, others depict damaged, fractured and grotesque bodies entirely at the mercy of events.

Dana Shutz’s paintings, Singed Picnic (2008) and Reformers (2004), are bizarre tableaux from incomprehensible narratives, one in which the charred husks of picnickers are inexplicably burnt out of their pseudo-impressionist scene, and the other following their frantic attempts to re-assemble a broken body on a rudimentary, open-air operating table.

Narratively, Shutz’s work is difficult to follow: their human subjects are caught up in the mystery, and are accordingly lost and powerless.

Andra Ursuta’s Crush (2011) is a horrific cast sculpture of the artist’s own body which has been flattened, coloured the dark grey-blue of a rotting corpse, and then covered in pools of silicone that resemble seminal fluid.

The viewer has evidently arrived to witness the aftermath of some terrible, violent event, and the human body at its center is completely devoid of dignity and control.

Some critics have been disappointed by Body Language, perhaps hoping to discover a new generation of artists ready to reinvigorate representational art for the 21st century, but this critique seems to sidestep the point of the exhibition.

While some of the works on show may lack technical mastery in the depiction of the human anatomy, the exhibition successfully explores how the human body, as a repository of ideas rather than solely as a figurative subject, is being treated in contemporary international art, filtered as it is through Charles Saatchi’s taste in brazen, sledgehammer metaphors.