Seeing the collection of works displayed together in ‘Britain Goes Pop!’ is a novelty, even for London, and it’s effective. There seems to be something familiar about the works in the Christie’s exhibition, which opened 9 October. However, it is the first exhibition comprised solely of British Pop art to ever be shown in London, and it is this fact that makes ‘Britain Goes Pop!’ so important.

Many of the key works of British Pop Art have been shown frequently in the past, though usually in larger contexts. By focussing solely on British artists, Christie’s has tapped into a distinct, cheeky and often patriotic side of the movement. Not only are the pieces individually strong, the collection is large and varied, and representative of an impressive catalogue of names including Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, David Hockney, and Allen Jones.

Yet throughout ‘Britain Goes Pop!’ there are many images, names and concerns that are topical in dynamic London today. There is awareness and uncertainty over the cult of celebrity, anxieties over war, worries over commercial culture, advertising and consumption. There are familiar brand names throughout — Coca-Cola, Kellogg’s, Aston Martin and Colgate. There’s the uncertain regard for other countries and the prevalence of America in popular culture. Sex, in varying degrees of sensuality, is everywhere, and both the girl-next-door and the leather-bound stunner are fetishized, criticized and adored.

Hamilton, one of the pioneers of Pop Art, put his own definition on the movement in 1957, writing that it is “popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business.” ‘In Britain Goes Pop!’, many of the pieces fit the description perfectly.

Hamilton’s own series I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas, for example, is made up of retouched images of Bing Crosby. The resulting screenprints are at once recognizable, delightfully colourful and yet slightly unnerving. Caulfield’s large Landscape with Birds (1960) seems to be one of a series of decorative prints, but is actually a single painting, large, strange and satisfying. Allen Jones’ Table, Chair and Hatstand (1969) demand attention with their size and brashness. These three works are comprised of slightly over life-sized sculptures of women in skimpy vinyl outfits contorted into their respective furniture positions. Even now, more than 40 years after they were created, the furniture calls forth an immediate, visceral reaction.

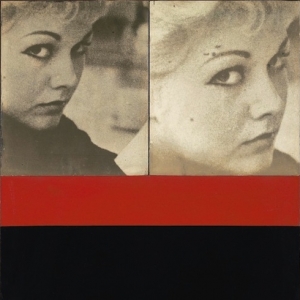

However, while a lot of the sexiness, gimmicks and glamour are preserved in these pieces, in some cases, transience and low-cost have taken their toll as well. Paper peels at the corners on Paolozzi’s 1940’s collages, newsprint yellows on Peter Blake’s Locker (1958) and even the print on Colin Self’s Leopardskin Bomb No.1 (1963) has faded.

Christie’s has given the aging-yet-current art the treatment it deserves. Set in the auction house’s new Mayfair space, ‘Britain Goes Pop!’ is a new concept for the auction house. Although their Post War and Contemporary Art sale is approaching, only a few of the paintings on show will be up for sale, making the exhibition distinct from saleroom viewings. Instead, Christie’s collaborated with the artists, the artists’ families and private collectors to put together an expansive show comprising three spacious floors. There is room for a number of paintings, drawings and collages, plenty of Antony Donaldson’s bathing beauties, Paolozzi’s large tower constructions and even a small cinema room.

Arranged thematically and chronologically, the information provided is occasionally difficult to follow – labels are stacked up together and tucked away in corners – but it makes the viewing that much better. Matching titles to images, moving around information and looking across other images back to the one you were initially interested in all make for positive, active viewing.

However, with works like these, there’s little need to coerce interest. Friendly and familiar, sharp and surprising, ‘Britain Goes Pop!’ is fascinating already, and well worth a visit.

So what does it mean if all these things are still so familiar? It could mean that these pieces were not created so long ago as we might think. Not only are David Hockney and XX still alive, they are also still revolutionising through ever-developing media.