Typically a cheapskate at art exhibitions, I couldn’t help but flinch when handing £7 over the front desk of the National Portrait Gallery. As I walked through the halls, I wondered how I could justify each spent pound through seven reactions to various stages of the exhibition. My responses to the representations of Dame Laura Knight’s enviable life made this task easy: each framed painting was a window into her colourful life. Her talent was limitless, but as the first woman admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts, that’s hardly a surprise. The exhibition was not so much a display of her talents, but a tribute to the spirited, pioneering woman who stood behind the canvas.

(£1) Knight’s journey started after moving to Cornwall with her husband Harold, where she painted portraits outdoors in a markedly impressionist style. Moving away from the expressive brush strokes of the Impressionists and adopting Realism, this would remain her signature until death. The paintings are vibrant, emotive, and evocative of freedom, and resonate long after you leave the gallery space.

(£2) As her love of painting behind the scenes was born backstage, intimacy became the focus of her portraits. Knight began to paint ballerinas in their dressing rooms, in attempts to capture the dancers as the women beneath the performers. A woman herself, Knight had been prohibited from painting realistic nudes whilst at art school, and so the graceful stature of dancers satisfied her thirst for rendering form.

(£3) Although Knight rejected modernism in art, she embraced contemporary life and subjects of personal relevance in her painting, evinced through the vibrancy of her work. She traveled to The Johns Hopkins Hospital at a time when the United States was racially segregated, painting African American nurses and patients ward. One nurse brought Knight to a Civil Rights rally, where she was the only white attendee.

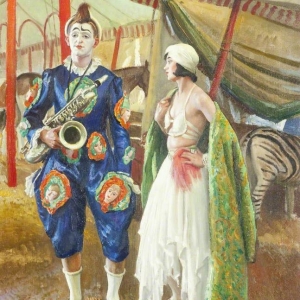

(£4) This same spontaneity led her to the circus upon returning to England. Knight painted hidden scenes of clowns off-stage, posing in their natural attitudes, offering sincere and unassuming glimpses into their distinctive lifestyle.

(£5) Following the up-and-go circus lifestyle, Knight met with the Smiths, a gypsy family living and working on a farm in the countryside. She hired an old Rolls Royce as a makeshift studio and painted a series of gypsy portraits inside it. Particularly interested in femininity, Knight paid close attention to the family’s matriarch, who sat for her many times.

(£6) Knight’s style and aims shifted with the outbreak of war. She lost a great deal of her artistic autonomy, and as a prominent British artist she was commissioned to create propaganda in paint, primarily of female factory workers. She also painted uniformed soldiers and scenes of the Nuremberg Trail Trials upon request.

(£7) After the war, Knight continued painting commissioned portraits, only this time as a member of the Royal Academy — thus achieving her life dream. Coming from a childhood of poverty, Knight elevated herself to national prominence, whilst pioneering for women in the arts. Patronage was lucrative, and she continued painting portraits in her St John’s Wood studio until her death in 1970.