What do we imagine when someone says “Manet’s portraying life”? The new exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts takes us on a journey to reveal completely new perspectives of Manet. Not only is Manet presented from a personal perspective, his life is put on a pedastal to be assimilated from numerous viewpoints. But, there is still more on offer. Thanks to the setting of paintings within the context of a gallery itself, we can see connections otherwise not so blatant. Each room is dedicated to a particular type of sitter, and therefore successfully emphasizes Manet’s depiction of the social situation.

The curator, Maryanne Stevens, explains that the exhibition is above all retrospective and provides pieces of work from the beginning as much as from height of Manet’ s painting career. This key aspect is rather unassuming, due to the non–chronological order in which the paintings are organized. That is why I recommend to the potential viewers to go through all the brochures and information available on the website prior to attending the exhibition itself.

The exhibition is sequential rather than chronological. The first room out of eight is dedicated to portraits of his family. This is a very good choice because initially, we see Manet’s heritage, and can figure out the meaning of his following works in relation to those he holds closest. The mood of the exhibition – to know the master behind his works – the central topic of identity in Manet´s exhibition is determined from the outset. After the first room, on display is probably the most famous painting of all in the exhibit – Music in Tuilleries Gardens, 1862. This is a great position – still fresh enough to fully engage with painting, but softly introduced to the source of the Music. Interestingly, this painting deserved its own room, serving to intensify the point of the entire exhibition. Music in Tuilleries Gardens, 1862 is a portrait of blatant social observation; a modern piece of art with hints of Impressionist shading and colouring. What’s more, groups of his closely related colleagues, friends, intellectuals and family indifferently posing as someone unfamiliar. It is simply the idiosyncratic Manet – a dilemma of sitters is present, hiding his numerous passions.

Other rooms are dedicated to groups of people as well, including his intellectual colleagues, status portraits and women. There are actually two rooms dedicated to women, one to a particular woman – Victorine Meurent. With her he painted the most beautiful and profound pictures: Olympia, 1863 (not in the exhibit), Dejeuner l’herbe, 1862 and The Railway, 1872. Victorine Meurent was the most favourite model of Manet. She deserved her own room probably because of her inspirational personality (and also because of the sheer volume of her portraits). Manet was strucked by her from the first moment. This much is obvious in all of the paintings. It was either her strong charisma or Manet´s passion for her which made the paintings so great – or probably a combination of both. This helps us understand how inspiring women were for Manet. We probably wouldn’t realize this fact that easily within any other setting. One crucial aspect of the installation was the aforementioned room outlining Manet’s life – personal and as a painter.

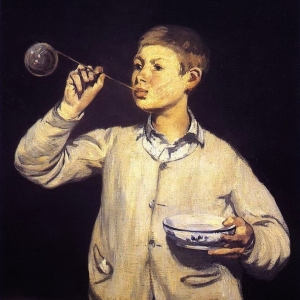

Despite the exhibition being tiny – only few more than 50 pieces – it is very insightful, and represents a new emerging attitude surrounding Manet’s paintings. Is his intention to depict his sitters as actors, or does he want us to know who they truly were? The best example of this dilemma is Boy Blowing Bubbles, 1867. In this painting Manet depicts the most portrayed figure of his all work, also a family member. Leon Koella Leenhoff was a son of Suzanne Leenhoff – Manet´s wife. Interestingly, neither Manet nor his wife admitted this family connection to friends or in public. In the Boy Blowing Bubbles, Leon is depicted with bubbles, which were an allegory of death. This depiction of Leon with a memento mori describes inevitability of mortality popular in 17th century Dutch paintings; or more specifically relating to children, fleeting youth and loss of innocence. As one of many, the painting is ambiguous and evokes mixed feelings. If we are ignorant of the emotional connection between the model in the painting and Manet, it would seem solely symbolic of the memento mori. However, as Manet surely understood Leon´s personality quite well, one can deduce that he wanted to make a portrait of Leon himself and embrace his personality traits. Leon´s expression is very decisive, mature, yet at the same time soft and transcendent. These traits would fit both memento mori reasoning and the personable one. However, the scene is more realistic than typical memento mori, accentuating the figure of the boy in white dress on the black background. Therefore, it is difficult to decide the thoughts of the creator at the time of painting. This topic is typical and central for the whole exhibition. Where does the personal end and the artistry begin with Manet´s portraiture? These questions arise whilst looking at the paintings and pondering itself provides a deeper look into the artist´s mind.

There are many highly valued and interesting paintings in the installation, but one which particularly caught my attention. It draws mainly from Impressionism, and therefore not so stereotypical Manet, as he attempted to have his works accepted by The Salon, who valued traditional painting techniques. However, we can see his passion for painting an evocative representation of life in this painting, and how much he refined in order to be acclaimed. As we glance at the picture, the first thing we see is a well-dressed woman with her child enjoying a peaceful afternoon in the garden. However, on the side there is a man taking care of some plants. The gardener is Monet and the painting’s title self-explanatory: ‘The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil, 1874.’ Also present, a cock and a chicken. Poultry running freely in the garden suggests the land is rural. Monet is depicted here as a family man rather than an artist. It is easily recognizable as Manet’s portrait due to the clean, blank ‘whiteness’ of the woman’s dress, contrasting with grass. The woman is his wife, holding a fan, implying bourgeois leisure, creating paradox between her actions and the presence of cock and chicken. The lady seems to be amused by Manet painting the situation. She’s looking at him, while Monet doesn’t want to be painted and is trying to ignore the artist. Their son appears too quiet, serious and still, which is strange due to his age. There is a suggestion that he is the embodiment of Manet’s perception of rural life. It is painted ‘en plain air’. The light is bright and we can see the effort to catch the moment. Blurred lines of the brush’s movements add to the development of Manet’s style and his liberation from conventional techniques. Manet did not wish to exhibit this painting because it was not acclaimed in The Salon, but possibly also because the content of the painting is pretty, personal and impulsive.

Overall the exhibition is intelligible and insightful. The most valued element is certainly the new attitude which The Royal Academy of Arts offered. It is difficult to find something new about an artist who was analysed from every possible aspect and point of view. And that is the reason why Manet: Portraying life provides enriching experience for everyone, from an art layman to an art expert.