Visually expounding the experience of psychedelia is nothing new. We have all seen and recognize the lurid, technicolour stylisation of altered consciousness; we’ve all gone gross-eyed whilst trying to trace its kaleidoscopic intricacies. Confronting us with bright, fluid murals, complex automatic sketches and mixed media installations, Reflections from a Damaged Life is no different. Seeking to express psychedelia through unexplored visual potential, works purport to tap into the nether regions of the subconscious in ways that add a novel depth to pre-existing pools of meaning.

Dubiously labelling works as “artistic experiments” is a painfully ambiguous premise. Yet the exhibition cleverly covers all of its semantic roots: an experiment is an attempt, a preliminary collection of trials from which to draw conclusions. Whatever the outcome, nature, or consequences of an experiment, it will always be relate directly. Technically speaking then, we cannot accuse the exhibition of failing to deliver.

Spread across three floors, works vary in medium and style incorporating film, performance, installation, photography, screen prints and drawing. The mass of information conveyed via multiple visual variables overwhelm viewers; perhaps an allegorical reference to the scattered and over-stimulated mindset induced by psychosis. We can’t help but second guess ourselves as we search for consistency amongst these snapshots of distorted reality.

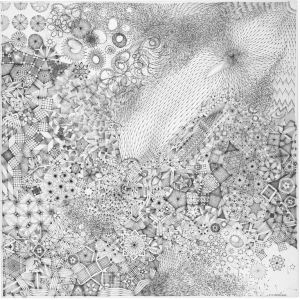

In Tanadori Yokoo’s Wonderland, we see cut-out human figures and shapes float across a wide beam of light coloured like a dark sunset. They are flat, devoid of colour and meander aimlessly across the plane, completely at the mercy of their surroundings. Wonderland then is injected with clever irony: the bright colours illustrate the scene as fantastical and emotionally charged, whilst radiating a sinister authority. Through figuration, we’re encouraged to position ourselves within the situation, swimming amongst the lost shapes and nonsensical forms. Here, Damaged Life is a realm in which the subject loses control, and as we scan the impossible intricacies of pattern and colour, can tangibly feel their fear.

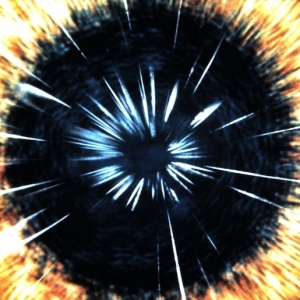

Pierre Huyghe’s performance piece L’Expédition Scintillante similarly engages with ideas of control, but is unable to provide the same calibre of critical fodder. A sequence of light dances between two parallel, horizontal boards as classical music plays and thick, white smoke billows out and slowly fills the room. Our unique responses to stimuli colour and sound merge with the visual prowess of the smoke, characterising the experience of psychosis as a collection of isolated sensations. Directly placed within this simulation of psychological space, we consider psychedelia on a purely sensational level. Whilst Huyghe diligently articulates particulars of psychotic experience, he is fails to offer us more than just a sensual description of it.

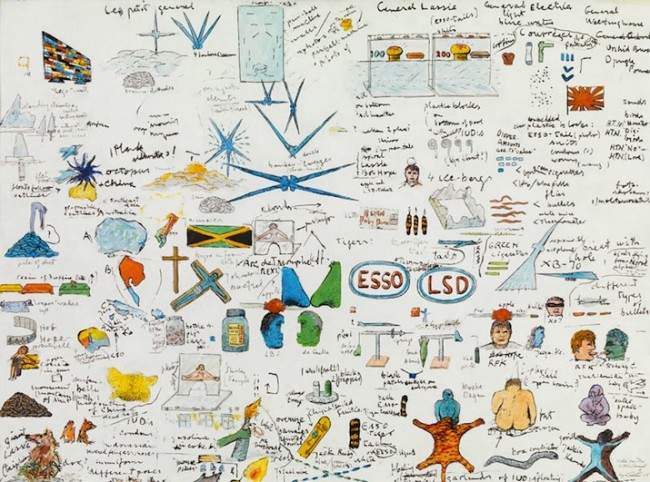

It is here that Öyvind Fahlström’s The Little General is a particular triumph. Whilst seemingly random, each component of the large, mixed-media installation is pregnant with meaning, documented cleverly by accompanying works Notes for a Little General. Comprised of manipulated media images, toys and vertically placed sections of clear plastic, water and snatches of vivid colour, Notes remind us that every component of the work has been deliberately placed. The viewer is urged to consider psychosis not as scattered consciousness, but as a semantic journey through carefully constructed chains of associated meaning. The Little General delineates the experience of psychosis in a way that is tangible and exact, pushing us to think critically about psychosis as a series of cognitive responses. Psychosis may, after all, be described as a set of chemical reactions in the brain.

Whilst Reflections from Damaged Life succeeds in articulating the experience of psychedelia, it fails to negotiate larger ideas of consciousness and expression that exist on more sophisticated, critical levels. Works are visually arresting, intense and exceptionally executed, but are automatically branded “experiments” or “exploratory”, appearing as fact without the perceptible excess that invites profound, critical scrutiny. Use of established ideas and aesthetics linked to expressions of psychedelia similarly prevents departure from familiar knowledge.

It is for this reason that the exhibition cannot surpass its referential quality: we’re shown a collection of artistic experiments that explain what a psychedelic experience looks like, but do not push us to conceptualize or interrogate what it entails on a more lateral level. Purely as an exposition, Reflections from Damaged Life is effective, engaging and stimulating, but in its ambiguity fails to lead us down tangible avenues of intellectual or critical depth.