Although there is a certain organic beauty to her recent bronze sculptures, Lucas’s main talent lies not in crafting exquisite objects but in arranging her own creations alongside banal objects to make jarring, provocative images. With individual works arranged in a cluttered, seemingly haphazard configuration, this entire show functions as one huge, relentless installation. Wherever the viewer looks, there is something uncomfortable, disturbing or viscerally disgusting.

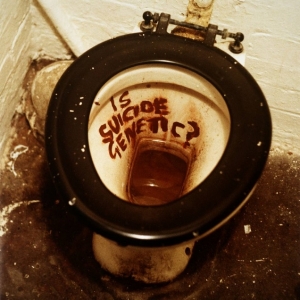

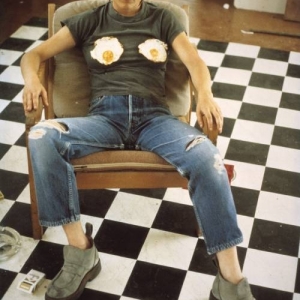

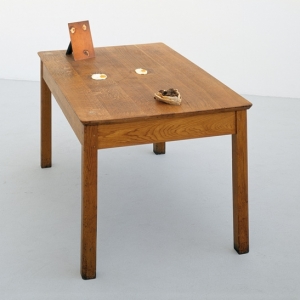

Turn away from Fried Eggs and a Kebab to find Bitch; Lucas’s 1995 creation where a desk, a t-shirt, two melons and a kipper represent a woman on all fours. Nearby, a filthy toilet bowl asks through the medium of excrement-coloured paint, Is suicide genetic? Meanwhile on the wallpaper, disembodied penises float in a sea of multi-coloured soup. Lucas, one of the very few photographed faces to appear in the show, presides over this chaos from self-portraits on all four walls, with her trademark expression of disinterested arrogance.

Lucas comes across as a headstrong artist with ambitious feminist goals. At its best, her work successfully challenges sexual objectification, ridicules the notion of the phallus as a source of power, and deconstructs the stereotypical British middle-class obsession with good manners. By reappropriating crass references to genitalia in such an overt way, Lucas exposes as farcical the prudish bourgeoise tendency to reduce women (and men) to a collection of sexual body parts.

The secret to Lucas’s success is her disarming use of ridiculous, comic metaphors to discuss important subjects. Her work is simultaneously too brusque to be taken as literal, and impossible to ignore.