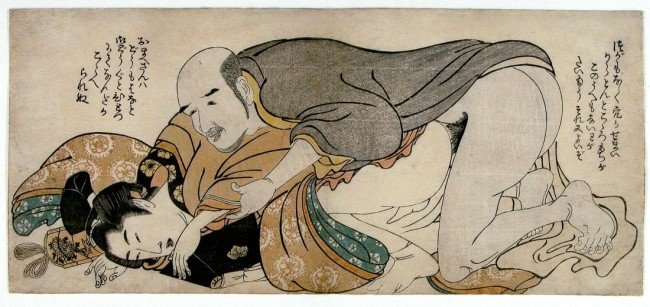

The British Museum’s exhibition Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art opened on the third of October. The trailer for the exhibition features the tagline ‘inspired Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin and Picasso,’ and a breathless female voice whispers ‘Shunga’ at the end, presumably in order to excite a prospective audience member into eagerly booking tickets to the exhibition of ‘taboo’ art. Shunga, incidentally, is the Japanese term for erotic art, though it directly translates to ‘spring pictures’. Notable artists include Utagawa Kunisada, Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai, famous for The Great Wave Off Kanagawa.

All of this is nothing new, especially since these works have been around since the sixteenth century all the way through to the nineteenth, produced mostly by ukiyo-e, or ‘floating world’ artists, whose medium was commonly woodblock printing. However, in the wake of yet another Victorian belt-tightening coupled with a self-righteous policing of the Middle East’s ‘deplorable morals,’ it’s hardly surprising that an Eastern heritage of representing sexual practices should be under our magnifying glass once again.

It was when Picasso ventured into a smelly, dank part of Paris and wandered absent-mindedly into the ethnographic museum in the Palais de Trocadéro that he experienced an ‘epiphany’. The result was Demoiselles d’Avignon, a jarring representation of Catalonian prostitutes, each more fearful than the last, each sporting a more disjointed, warped physique and a more frighteningly sharp, malformed face. Several art historians have said it betrays the artist’s phobia of women and their potential for sexual ravenousness, the destruction of a man’s sanity, emotional well-being and self-control, and even killing through venereal disease. It is both a disgustingly unfair and irresistible metaphor- to be eventually destroyed by one’s own lust. Is it a coincidence that this painting was produced in the midst of and is the most well known of Picasso’s ‘African Period’ works, or that the terrifying faces are inspired by Iberian and African masks?

Conversely, when Manet’s Olympia was first exhibited at the Salon in 1865 it was laughed out of the building because it had the audacity to represent a woman who was clearly of the modern age, who was entirely naked and not the acceptable ‘nude’, who stared straight out of the canvas into the eyes of her viewers and who worst of all, had white skin. This caused a great deal of discomfort, which is attributable to the 19th century. Nevertheless, when Ingres unveiled Grand Odalisque, fifty-one years prior in 1814, a painting that was similarly influenced by Titian’s Venus of Urbino; who is just as pale as the moll of Montmartre and whose eyes do meet those of anyone who gazes upon her; she was met with admiration and approval. However there is only one major difference between the two women, and that is that the former ‘promiscuous girl’ is not from the East, whereas the latter supposedly is. This is only made clear by the titles, incidentally, Olympia being a recognisable alias for a Parisian working girl whereas the word ‘odalisque’ concretely referring to the servants and concubines in a Turkish harem. Not to mention the very fetching turban atop the head of the ostensibly Eastern woman.

The reason for this is because the ‘Oriental Other’; more effective than mythology, literature or modern life; is an acceptable conduit for revealing sexuality in art, because it is in the realm of the ‘unknown’. It is delightfully sensual because it feels separate from our own lives and this provides us with a much-needed escapism when we can see our ivory towers crashing down all around us. Heaven forefend that a Western couple, either modern or otherwise, can be depicted entwined in a loving embrace, with clothes being torn off and genitals being clearly visible, not to mention any unsightly hair or laughable expression of exaltation without an overwhelming feeling of repulsion, hilarity or embarrassment being felt. And be sure not to forget the clarion calls of ‘porn’ which would undoubtedly follow, and you can certainly forget an illustrious institution such as the British Museum ever exhibiting porn.