Britain is quietly home to one of the world’s greatest collections of Old Master prints and drawings. Not that The Young Dürer (until 12 January 2014) at the Courtauld Gallery in London limits itself to the institution’s permanent collection. Instead, an impressive array of international loans allow for a satisfying sense of comprehensiveness.

Albrecht Dürer’s legacy is one of supreme self-confidence. His oeuvre is often perceived as a keystone in the emergence of High Renaissance, and a crucial link in the artistic fossil record, bridging the German and Italian traditions. However, this modest exhibition is altogether more nuanced. The works at The Young Dürer focus on his formative years, the so-called Wanderjahre (1490–94), during which the 19-year-old artist travelled around Europe, honing his craft.

The results are twice removed from the usual plaudits of genius and perennial concern for Dürer’s relentless self-promotion: once through his tender age, which reveals a young man finding his feet at a time of exceptional artistic production, and twice through his exploratory and relatively unfettered sketchbooks.

Renaissance drawings have come to be appreciated as the product of a comparatively unselfconscious creative process. Whether accurate or not, one double-sided drawing from the early 1490’s typifies this perception. The work reads rather like a private window into Dürer’s mind. Pleasingly chaotic, the artist juxtaposes a Virgin and Child with a more carefree sketch of a giant hand hovering in the sky. Unlike his celebrated finished paintings (of which, sadly, very few reside in Britain), his drawings are presented here as a form of proto-art, through which we may discern the seeds of greatness.

Mein Agnes (c.1494) is another good example of an ‘uncalculating’ Dürer. This rapid and informal sketch depicts the artist’s pensive looking young wife with a rare intimacy. We can only speculate as to the original purpose of the drawing, however, the apparent autonomy of the image unwittingly, and superficially, anticipates later art liberated from the shackles of patronage. This kind of subjective and retrospective comparison is key to the popular enjoyment of Early Modern drawings.

Aside from Dürer’s process, this exhibition is also keen to demonstrate that the artist did not exist in an isolated bubble of genius. He travelled in order to learn, and his antecedents number as many as his descendents. And non-more so than Martin Schongauer, whose works such as The Virgin and Child with a Parrot (c.1470–73), profoundly influenced the young Dürer. Schongauer, although in many ways a typical early Renaissance artist, embraced new printmaking techniques and grounded Dürer in the hard-edged German traditions.

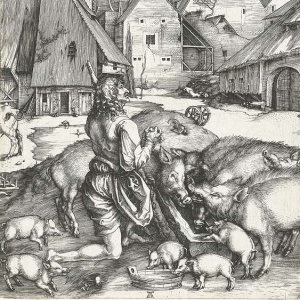

In the late fifteenth century, prints were a relatively new art form, and works like The Prodigal Son (c.1495–96) helped to establish Dürer on an international stage. This new technology allowed his work to be disseminated far and wide, providing a new means of income and unprecedented levels of fame. As such, Dürer became rather like a brand, complete with a logo (Dürer’s instantly recognisable ‘AD’ monogram). Thanks to the likes of Dürer and Michelangelo, this was a time when artistic personalities came to the fore. And, despite his relative immaturity, Dürer was already putting himself very much in the picture. Figures in works, such as Youth Kneeling Before an Executioner (c.1493) and Youth Before a Potentate (c.1493) tantalisingly resemble the young Dürer, while his characteristically psychological Self-Portrait (c.1491–92) reveals the kind of existential scrutiny we have come to expect from the artist.

From Dürer’s trademark self-reflexivity to his study of anatomy and burgeoning interest in antiquity and contemporary Italian art, all the High Renaissance hallmarks are present and correct on the Courtauld’s walls. However, The Young Dürer introduces a refreshing level of uncertainty to this most glittering and confident of artistic careers. Although we all know how Dürer’s story ends, this exhibition provides an enjoyable glimpse into the journey’s start.