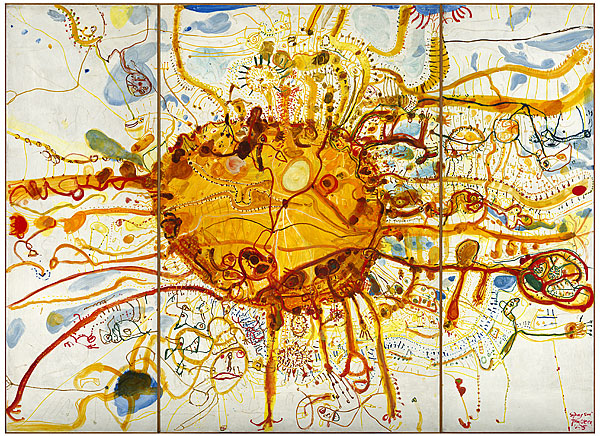

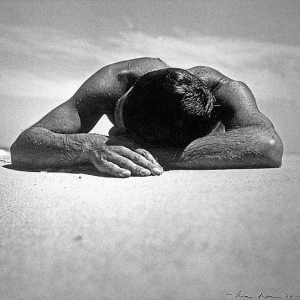

The atmosphere of the natural Australian landscape is a tangible thing. It can be harsh, isolating and uncompromising, yet life-affirming. It is the source of creativity, inspiration and imagination. It is our life blood. It is what every Aussie sees when they close their eyes, and smell long after being sucked back into the suburban sprawl. The Australian landscape as immortalized in the history of Australian art and holds a universal significance

As an Australian and a student of art, I find the abrasive criticism of the Royal Academy’s Australia exhibition extremely disheartening. Over the past 200 years, many great Australian artists have successfully recognized and employed the Australian landscape as part of a continuum: a way of connecting cultures and of relating past to present. Indeed, many of these artists are featured in the Royal Academy’s exhibition, yet the exhibition itself has fallen far short of potential. I seek to understand why.

Spanning thirteen rooms, Australia is the first large scale survey of Australian art in Britain for fifty years. It presenting a major opportunity for the National Gallery of Australia and the Royal Academy to express, “the distinctiveness of the Australian landscape, whilst considering the art historical developments and contributions of Australian art across the last two centuries.”

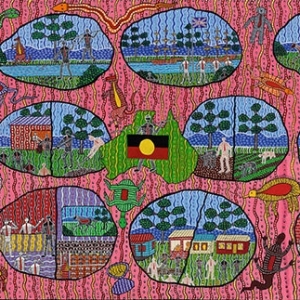

Criticism has slammed the choice of work, the selection of artists, the aesthetic caliber of the work and the curatorial narrative. In specific the awkward collision of tradition, modernity and contemporaneity has amounted to what The Guardian deem a “wobbly ride through the past and into the present.” The Evening Standard touted the Indigenous works on display as a “stale rejigging of a half-remembered heritage.” Australia’s colonial history, played out through representations of the collective relationship with the land, would always jar when shown with Aboriginal artistic traditions that date back tens of thousands of years.

The Royal Academy took on a herculean task in curating historical contemporaneity, and the enabling dialogue used by the curators of the Australia survey exhibitions to be commended. Channeling two hundred years of Australian art through the landscape motif however is bound to leave aspects of Australian art history deprived. The significance of the works has been diminished due to the lack of context, specifically with works presented as part of a hurried novelty checklist. This is hugely problematic, particularly for an international audience, many of whom may have had no previous exposure to Australian art.

In its ongoing quest to locate itself within the change of ever-widening socio-political frameworks, art’s relationships to broader contextual forces and to prevailing understandings of historical forces are crucial to contemporary curating. Employing novel terminology such as ‘Modernism, 1920-1950’ and ‘Elizabethan Post-Colonial 1950–2013,’ Australia, rather than glorifying in a mythologized national identity, leaves artistic representations of our land in a “dystopian limbo.” The curators here seem to have stayed loyal to the national and local mandates of the traditional contemporary art museum. This strategy challenges nothing. Indeed, Australian critic for Fairfax Media John McDonald proclaimed that he found it “ hard to believe that Australian curators could put such rooms together and feel satisfied with their efforts. It was clumsy. It was provincial. A great opportunity has been wasted.”

Contemporary curating has, as its driving passion and distinctive mission, the task of provoking its audience into thinking differently. Despite the failing curation of such a monumental exhibition, the idea of an immutable connection between Australian landscape and fantastical Jurkapa (Dreaming stories) has a key mode of expression in the visual arts.

I hope that in the future, the history of Australian art will be presented to the world not through a tunneling of analogous motifs, but rather as an exploration of how we grapple with issues that we face as a nation; how we have confronted the trauma and successes of our past, and how we imagine our future as a nation whose identity is fractured, non-linear, and ever-changing.