During her first year at Goldsmiths in 1973, Baker had to exhibit her work, but was worried about its reception against the more traditional style of the other students. She made jokes about her work, causing her to be perceived as “funny” and “weird” in making people laugh. Baker was extremely upset about this, and then decided she could not be like other artists. Instead, she was to focus on her internality, in way of her torments, personality, opinions, concerns and experiences, deciding that humour would comprise an integral part of her work. Laughing at her own helpless situations was a way for her to deal with certain issues and has become a valuable method of communication for her, made apparent in many of her artworks. This is similar to Wilke, as both artists mock their illnesses as a coping mechanism. Wilke’s poses and the situations she photographs herself in mock how we feel we should behave and think when seeing such images, and force us to question what ‘real’ beauty is. Baker makes the audience feel uncomfortable by insulting the mental health system, and creating tension in the way she presents herself in with regard to her health issues. Mental illness is a taboo subject, and many do not know how to react when they find out someone suffers from it. The fact that Baker is making fun of herself through her performances confuses the audience as they consider whether they should laugh along or not. The content is definitely not a laughing matter, but Baker really pushes the audience to question their morals and understanding of the subject.

“Pull yourself together” is an important piece of work for Baker, as it was the first time she had created work specifically about mental illness. The performance was prepared for mental health action week, where she made a mockery of the fact it existed. Baker was sat in the back of a truck with banners down the side spelling out in red letters, “Pull Yourself Together” and “In aid of Mental Health Action Week.” She was driven around London, shouting “Get a grip, Buck up now, Cheer up, Put a smile on your face!” to bystanders. Baker proclaimed that “it was delightful to bawl these insults, of which I’ve been at the receiving end so much of my life, at crowds of people with such irreverence.” People would laugh at the act of yelling such statements but when seeing the mental health banner, would clearly stop to think about the performance as a whole and what it meant. Again, Baker makes the audience question their understanding of mental illness. By shouting out statements that she has heard all her life, she reverses the roles by putting the audience in her shoes.

Another of Baker’s 2004 performances entitled “How to Live” saw her standing on stage in the role of a psychotherapist with a 11-step recovery plan. Her patient was a frozen pea. The audiences were incredibly entertained and the shows subsequently sold out. The audience laughed along, temporarily forgetting there was anything wrong with Baker. She wouldn’t get taken to an institute or a hospital as she was now the one wearing the white coat, appearing in a position of control over the situation. Here Baker was communicating how we feel safe in the hands of a person in a uniform, whether it is the police, fire fighter or doctor; we do as they say because we feel they know best. However, they are only human, and can take advantage of us as much as the next non uniformed individual. Baker felt she was treated badly when she was in the mental health hospital, ignored by nurses and treated as if she was not in control of her thoughts.

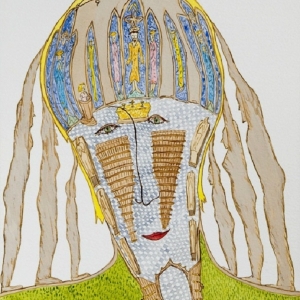

Baker began her well known diary drawings in 1997 when she became a patient at Pine Street Day Centre. The drawings were originally private, but soon became an increasingly important tool to convey her more complex thoughts and emotions to mental health professionals and her family. Baker describes them as “survival mechanism, a way of hanging on during such an alarming time, and they gave a focus to my time and experiences.” They gave her some control when in reality she felt as if she was very much out of control. Baker believed she would be at the day centre for three weeks; she remained there for five years. The drawings have been praised for successfully communicating Baker’s experiences of mental illness. In response to this, Baker stated that “mental distress is largely invisible and anything that increases knowledge seems worth a shot.” It wasn’t easy for Baker to begin communicating in this way, describing her creative process as follows:”I would look at a blank page – and see such anguish and pain – and search for a subject.”

On “Day 43,” the drawing shows Baker made up of bricks, with sections of her head and arm on the floor, showing that she feels both her physical and mental foundations to have been broken. The phrase ‘breakdown’ expresses extreme mental anguish, from which you would need to rebuild yourself ‘brick by brick.’ The drawing clearly shows that she feels disconnected and damaged. Diary entry 543 is also an interesting one, showing that she feels as if she is a divided being, appearing as someone who presents themselves to the world as different to the person ‘behind the mask.’ There are two body shapes present in the work, with the ‘hidden’ body being double the size of the outer body. This could be due to the anxieties faced resulting from medication, also shown in “Diary entry 397” where two bodies are drawn, one titled “Pre Medication” and the other “Post Medication.” The first is slim and almost disappearing, the second is overweight, sweating and seemingly uncomfortable. The fact Baker put on a lot of weight due to her medication is documented a lot within her diary drawings and is obviously a cause of great distress to her.

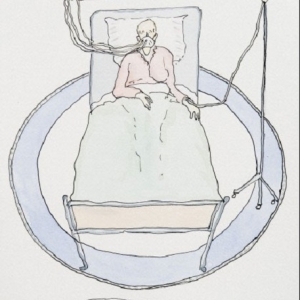

One diary drawing shows Baker’s naked body covered in tiny neat cuts as means of representing her acts of self-harm. Although the diary drawings are a success for Baker, she looks back on some of the entries with disgust at how she managed to cope: “at that time, self-harming wasn’t written about. What I was doing was atypical for a woman of my age and I was massively ashamed. I could see how awful it was. And yet what I could do was make a lovely picture out of it.” There are many entries which focus on the psychiatrists, nurses and psychotherapists Baker saw. These images represent her feelings of utter hopelessness, suggesting how the patient can be drowning in severe mental distress yet still can somewhat control what the professional can see, as if protecting them from the truth of her illness. Within a lot of her drawings, it seems that the health professionals are unable to see or understand the true state of their patient’s emotions, which further alienates the two parties from each other.

This is in stark contrast to Wilke’s work, where every little part of her illness is on full show, whether it is the side effects from chemotherapy including her hair loss, the weight she put on or her bed-ridden status. Wilke’s photographs show the raw truth about how cancer destroys the body. Because mental illness is not a physical illness, it is harder to understand what the patient is going through, and the only way professionals can gain an understanding of it is through the patient talking about their experiences. This is why Baker’s diary drawings are so important: they communicate with the viewer the reality of what she is suffering. We cannot see how the illness is affecting her mind, but the drawings help us to understand the extent of how the illness is affecting her.

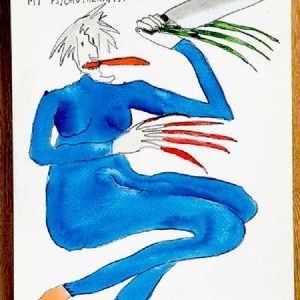

Diary drawing 165, titled “My Psychotherapist” explores the relationship between the professional and the patient and shows the risks present in this dynamic. The drawing shows the psychotherapist to have elongated talons at the end of her hands, a knife in her left hand and a blood red tongue which sticks out disturbingly. These additions show that the power of words can be hurtful, offending and can cause even more distress to the patient. This illustrates the problems of the mental health system, and how professionals can treat patients with mental illnesses. Without experiencing this system yourself it can be hard to understand what really goes on, so the drawings are an important tool for the viewer to construct an understanding of what the patient went through.

The drawings and performances are also important to Baker from a therapeutic point of view. Not only is she communicating her experiences to the audience; she is using art as a way of coping with the illness. Her constant use of humour makes the topic much more light-hearted and can be seen as an escape from her inner demons. Wilke’s work could also be seen as therapeutic, the fact she is choosing to publically show every part of the illness and what the cancer is doing to her body means she is making the disease less personal, and perhaps then not as ‘real.’ It is now a work of art, and by seeing the photographs on the walls of galleries she may have felt better equipped to deal with it.