MM: What medium do you work with?

Tasos Pavlopoulos [T.P.]: I work with acrylics on canvas or on paper. I started using acrylics as a student, at the very beginning of my career, when one of my teachers introduced me to them in art school. Shortly after discovering acrylics, I dropped oil painting. Acrylics are cleaner, they dry quickly and don’t smell! The interesting thing is that whilst I work with acrylics I use oil painting techniques – I know it’s unusual, but it fits my style. I have never learned how to use acrylics properly and people often mistake my painting for oil painting.

MM: Could you tell me a little about your artwork and its evolution?

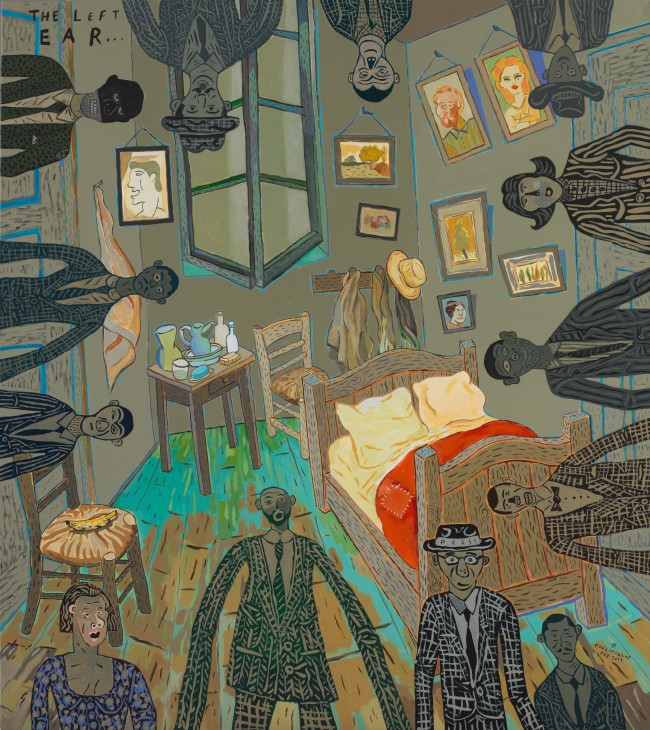

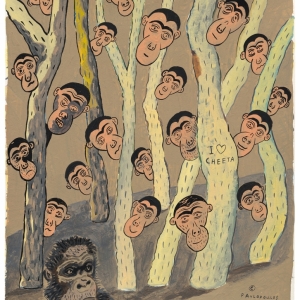

T.P: I reuse the same figures throughout my work – characters from my childhood such as Tarzan and Zorro, or everyday things that inspire me. The characters in my paintings represent my own cosmology. I drew my first drawing of Tarzan when I was a child. Much later in life, as I was looking back at my early drawings, I remember thinking that I was much better at drawing back then! I tend to paint anthropomorphic figures but I keep tweaking them, redesigning features, changing the shape of a nose here and there but they are still the same characters. As for the evolution of my work, it’s hard to tell. I think that my technique changes from work to work, and from exhibition to exhibition but it could be that nothing is changing at all! In earlier work, I spent hours painstakingly painting a series of little crocodiles which were organised geometrically. That painting required a lot of patience and thoroughness but today I don’t feel the need to be so meticulous. Perhaps I have become more impatient. I don’t know if it’s better, but that’s the way I work now!

MM: How would you describe the series ‘Happy Days’?

T.P: The series came before the idea. I wanted to work with a wrinkled effect, because I liked the aesthetical effect on printed paper. About ten drawings in, I realised that I liked the outcome and set to work to finish the series. You know how generally you get an idea first and then start painting? In this case, it worked the other way around: once the series was finished, I looked at the story behind the drawings. At first, I had no intention to charge it politically or talk about the economic crisis in Greece yet this wrinkled paper resonated with the social and economical situation in Greece. These are ‘Wrinkled Days’ in Greece, the title of the series is ironical. People don’t have jobs and the economic crisis has been going on for a long time. It also felt very appropriate to use printed paper, something affordable for people to buy in spite of the financial hardship.

MM: In your work you often allude to Surrealism and Dadaism, are you referring to your sources of inspiration or are you making a point about art today?

T.P: I guess that I have always been a Dadaist, even before discovering about Dadaism. I feel that my art relates to that movement in its ironical and satirical stances. In art, Surrealists and Dadaists have done it all before us. They are a source of inspiration for many, even in advertising. I just want to acknowledge the influence of these artists on my work, be it Picabia’s paintings or Duchamp’s ready-mades.

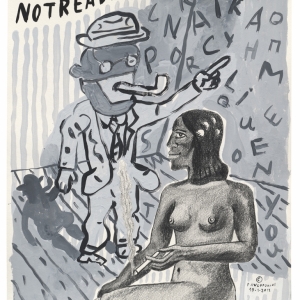

MM: What place has politics in your art?

T.P: I consider myself as an anarchist without belonging to any political alliance. Deep inside, my work has always been political. I have always been critical of what was happening around me, society, capitalism and the Bush administration during the Iraq War. Today my work is not as political. ‘Happy Days’, for instance, is an aesthetic work and I like it, but in the end it has a political element as well. The economic crisis in Greece has shroud Greek society in a certain misery. Even though what’s happening around you it may not affect you directly, it will affect people close to you – looking the other way is no longer an option. In the past, I used to voice my opinions but today I have gone underground. I hide the political meaning within my artwork and I am no longer obvious about it. In art and life, there is an overload of information when really we don’t know a thing – everything is a lie. It’s time for people to consider this.

MM: Are the recent events in Greece changing your perspective on the art world in your country?

T.P: I believe that nothing has changed. In my opinion there are very few good artists in Greece. We used to have people like Alexis Akrithakis [1939-94], but now the art scene is pretty bland. The art world has changed insofar as today’s curators and art dealers decide what good art is. They have become more important than the artists and it’s a shame. Art has become a business and the economy around the arts is like a machine, deciding the trends, absorbing the artists and turning them into mince-meat. The Greek art scene has not changed with the economical crisis, there is no Renaissance and galleries do not sell. The art world cannot remain the same, it needs to change.

MM: So what is the role of the artist in today’s Greece?

T.P: First of all, Greek art institutions should be rebuilt from the ground up. Greek people need to be better educated, to have good art schools, museums and galleries. People should be closer to art in general, doing everything they do in life for the love of craft rather than for greed. If we do things with love, our life will start improving. Politics starts from the very little things in life. I think that ultimately the role of the artist is to save himself and to be free.