The exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art opened at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery on 10 September 2013, and it travels to The Studio Museum in Harlem in November. Described as “the first comprehensive survey of more than five decades of performance art by black visual artists” (NYU press release), the exhibition intends to provide a critical history beginning with Fluxus and Conceptual art in the early 1960s, through to contemporary practices. At its opening, the exhibition included video footage from Mythic Being, Adrian Piper’s influential 1973 work of performance art. But, Piper has now asked for the work to be withdrawn, citing concerns over the marginalisation of black artists.

The exhibition chronicles the emergence and development of African-American performance art over three generations, with more than 100 works by some 37 artists. It highlights the work of artists from the United States and the Caribbean, from figures such as Dread Scott and Xaviera Simmons, and of course Adrian Piper.

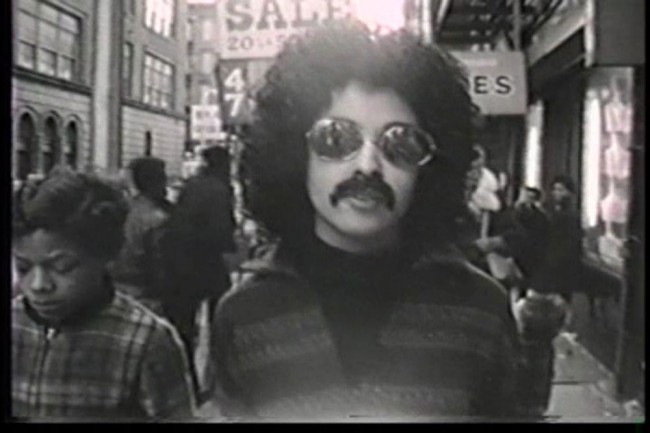

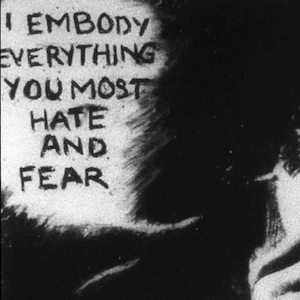

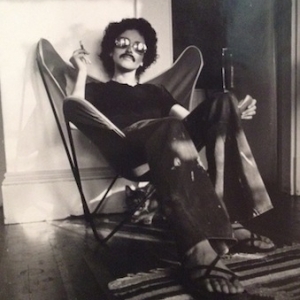

Adrian Piper is a celebrated pioneer of conceptual art. Born in New York City, she studied visual art and philosophy. From the 1960s onwards, Piper’s work engaged with the constructions of identity; how we view race, gender and class. In Mythic Being, she wore a false moustache, Afro wig, and wire-rimmed glasses to give a series of outdoor guerilla performances as this man, this mythic being. In the process she challenged people to classify her; to deal with their own preconceptions about race, gender and class.

After asking for her work to be withdrawn from the exhibition, in her correspondence with the Radical Presence curator, Piper argued that a better way to celebrate her work and that of other black artists would be to “to curate multi-ethnic exhibitions that give American audiences the rare opportunity to measure directly the groundbreaking achievements of African-American artists against those of their peers in the art world at large.”

Here, Piper is raising questions of how best to serve black artists and how we should deal with our own categorisations. Do we need separate exhibitions in which we can ensure that stories are told and that the public is presented with the bits left out of more main-stream exhibitions, or are artists better served by being included in multi-ethnic presentations? The second option risks the very marginalisation that Piper is worried about, missing out essential stories, whilst the first option could be seen as ghettoisation. The latter is Piper’s argument and it resonates her concern about the themes of marginalisation and otherness which have dominated her work.