In collaboration with the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Freer Gallery of Art/Arthur M Sackler Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution, the Dulwich Picture Gallery has organised the first major exhibition to be devoted to Whistler’s time in London, An American in London: Whistler and the Thames that runs at until 12 January 2014.

As a young man Whistler worked for the US Coast and Geodetic Survey where he learned to etch. In 1855 he left to study in Paris, before finally settling in London in 1859. It wasn’t his first visit to London, as a child he had visited his elder half-sister Deborah, who was married to the physician and etcher Francis Seymour Haden. Whilst still in Paris, Whistler issued a set of etchings, Douze eaux fortes d’apres Nature, which define what would be his concerns when working in the medium, the combination of naturalism and working on site. In some ways this is surprising, as etching, and the related dry-point, are hardly the most natural of mediums. They require the artist to acid etch, or scratch a copy plate, and the image comes out in reverse. As Whistler worked on site, this meant that his final images came out reversed. The advantage of etching for an artist like Whistler was its repeatability, and he would re-work plates until they were right.

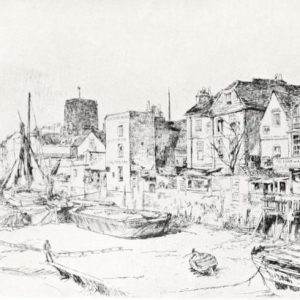

The first London etching on display was The Little Pool (1861), of which four different states were displayed, and acts as a fascinating insight into the artist’s working methods and concerns. The London that Whistler was depicting in these etchings has long since disappeared; his house in Chelsea might still exist but it no longer has a boat-yard just in front of it. It is this capturing of the rather ramshackle side of London life which makes the etchings so absorbing. They are major works of art, with Whistler displaying his sense of line and form, but they document as well. The major set of Thames etchings is the set A Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes of the Thames from 1871, though produced in batches from 1860. What might surprise anyone who is familiar with Whistler’s later work such as the Nocturnes, is how detailed and realistic these etchings are. Here is a strong grip on form and structure, but allied to a fine eye for detail with a clear concern for the sense of depth in the image. In addition to the etchings, there is also a period map of London and some stunningly evocative period photographs, some of which could almost have stood for models for Whistler’s etchings. The final etching of this sequence, Chelsea Bridge and Church 1871 displays far less concern over detail and more interest in general form, here the influence of Japanese woodcuts is beginning to be discernible.

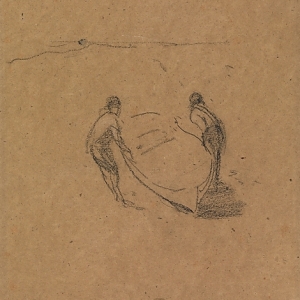

Whistler did not only work on etchings and a group of oil-paintings from the 1850’s and 60’s show the distinct influence of the plein air school of Courbet. But a painting like Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge 1859/1863, though it was painted from life, seems rather stolid compared to the etchings and the paint handling has not reached the fluidity of his later paintings of the bridge. On display is a photo by James Hadderley From the Greaves Boatyard, a simple image taken against the sun of a figure on the shoreline taken from the boat-yard by Whistler’s house in Chelsea. Next to it, the gallery has placed Whistler’s Two Men and a Boat 1872/76 which is almost the same scene, from a similar perspective. Whistler uses just a few lines on brown paper to create a complete image; here is the economy that we recognise from the later images.

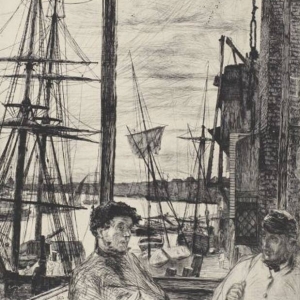

Later in the exhibition a letter from Whistler to the artist Fantin-Latour describing in wonderfully vivid detail the view from his balcony illustrates how Whistler was clearly entranced by the ramshackle sights and sounds of Thames life. Given the location of his residences on the side of the Thames, the river was an important feature of his daily existence, so much so that when visiting Thomas Wray, his printer, he was able to do a lithograph from memory in Wray’s office. His etching of Rotherhithe from the Thames set overlaps in subject matter and period with his painting Wapping 1860-64. Here, Whistler’s handling of the paint is far more confident than in the earlier paintings, the detail in this one positively sings. Next to it is exhibited Symphony in White No.2: The Little White Girl 1864, which is a far more soft-focus painting of his mistress Joanna, detail is less important here than colour and form. There is also an etching of Joanna, so frequently worked that her dress details are relaxed, soft and free, rather than crisp. Another important influence comes to the fore in the painting, a Japanese fan.

A crayon drawing, On the Thames At Chelsea 1870/73 is wonderfully free, creating an image with a few strokes without any worry over detail and topography. Next to this is displayed a trio of oil paintings including Battersea Reach from Lindsay House 1864/70. Here the image is pared down in a way that owes a lot to Japanese art; colour and form are important here rather than line. What is absent is as important as what is present. This applies to a picture of one of the wharfs, Grey and Silver: Chelsea Wharf 1864/68 which is far sparer than his previous pictures of this subject.

That this was not the only way Whistler was working is indicated by the 1879 etching, The Adam and Eve, Old Chelsea which is a brilliantly detailed evocation of the old pub, displayed next to a period photograph which shows just how accurate Whistler’s eye was. Nearby is a tiny but elaborate drawing Nocturne: Chelsea Embankment 1883/84 almost unique in Whistler’s output, full of hatched lines. From this point in the exhibition we move away from etching. Whistler didn’t stop entirely, but his London images now explore another technique, the lithograph. Lithographs are created by drawing with crayon onto stone or specially prepared paper. This is then inked and then printed. Whistler started using the technique in 1878 encouraged by his printer, Thomas Wray, and his first essays in the genre, Views of the Thames, were used for the journal Piccadilly. He returned to lithographs in the late 1880’s encouraged by Beatrice Godwin, an artist in her own right, whom Whistler later married.

Lithographs meant that Whistler could do freer sketches, capturing atmosphere rather than details. But the lithographs are also associated with a rather sadder episode, the final sequence from 1896 were done from the top of the Savoy Hotel where Whistler’s wife was staying during her final illness. His wonderful image, Nocturne: The Thames, 1896, his last nocturne, is bound up in his wife’s illness and is a powerful and haunted image. His oil Nocturne: Grey and Gold Westminster Bridge 1874/77 is a beautifully simplified image, a stunning study of form and colour with confident handling of paint. Whistler had been interested in painting darkness since completing some night scenes in 1866 and his first Nocturne dates from 1871. He later said of his Nocturne series that they were “an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest.”

As well as using Japanese objects in paintings, Whistler was influenced by the landscapes of Hiroshige and Hokusai. In the final room a pair of prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai are displayed, showing the remarkable visual links to Whistler’s images of Old Battersea Bridge, which he drew extensively in the period 1859 to 1879. There are detailed lithographs of parts of the bridge, The Tall Bridge 1878, studies in charcoal on brown paper which reduce the bridge to just a T shape, the Hunterian Museum‘s Battersea Bridge Screen, unfortunately only in photographic reproduction, and an etching from 1879/1880 which displays the bridge in glorious detail. These culminate in the Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge 1872. Whistler was an influential and prolific artist and the exhibition space at the Dulwich Picture Gallery is not large. By concentrating on his work in London, the exhibition has been able to give us Whistler’s art in a microcosm. Whilst including one or two iconic images, the curators have also sourced a wide number of others that help to illuminate Whistler’s development as an artist. And, in the etchings of the Thames, brought together some of his finest images and stunningly desirable objects.