The first solo UK show by Argentine artist, Sebastián Godín houses a collection of watercolour and wooden marquetry with the aim of bringing innovative Latin America art to London.

Collected Tales is being exhibited by the recently launched Cecilia Brunson Projects and showcases Godín’s practice, which is a departure from the prevailing conceptual and political tendencies of the time.

The artist favours a more playful experimentation of life and aesthetics through the use of everyday or traditional materials.

Upon entering the project space in Bermondsey, my first and enduring impression of Gordín’s magazines was in how absolutely alive they seem.

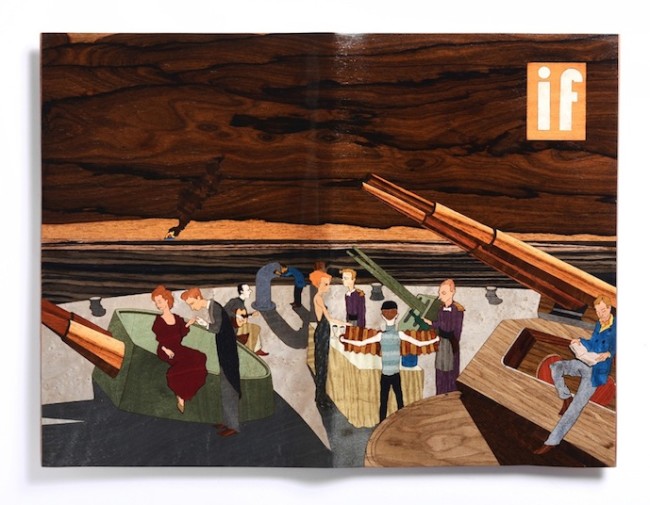

Arranged on five trestle tables, the magazine-sized wooden sculptures depict macabre, lugubrious, ironic and disquieting scenes from nether worlds derived from myth, fantasy, art history and pop-culture.

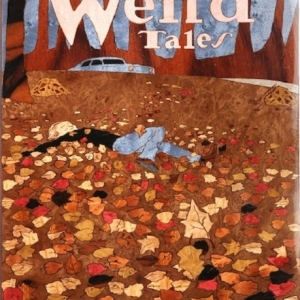

Whilst Gordín’s magazine titles originate largely from 1920s American pulp magazines, his images have little connection with those of their pulp originals.

Gordín’s graphic images are deceptively simple, plaintive black outlines that trace stained, brightly coloured veneers of wood. The colour palette – teak, jacaranda, maple, rosewood, laurel and ash to name a few – reads like an exotic roll call, rendering the pictorial plane of the front cover though the process of marquetry.

Gordín teases the wood to create gentle undulations as though aged by time and wear, creating an effect reminiscent of their pulp magazine counterparts. Vanished and polished, their surfaces are smooth and sensuous to touch, beguiling the viewer and demanding to be picked up and held.

Like the way children re-read their favourite books, poring over the images as though seeing them for the first time, Gordín’s magazines invite repeated handling and contemplation by the viewer.

Despite their likeliness to pulp magazines, use of wood imbues Gordín’s works with a life of their own. This adds to the character of the drawings: some are playful, and veer stealthily into the realm of black comedy.

A magazine christened The Labotomist depicts an ambulance-type ‘labotomobile’ driving into a richly-hued sunset, whilst alternate works have the flavour of a gothic fantasy, evinced in the ghostly, grey scene of Everybody’s Romance.

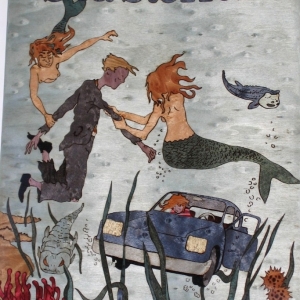

Others have the dreamy wistfulness of a fairy tale, with Sea Tales showing us a character lulled into the deep by two mermaids.

The vivid wooden magazines contrast with eight delicate watercolours depicting miniature magazine covers that are hung across the two perpendicular walls of the project room.

Reduced in scale, the watercolours provide a counterpoint to the wooden magazines: fragility against physical presence, transparency against density, and evanescence against verve. They also place the magazines in context, as Gordín first experimented with the series using this medium.

The overall watercolour effect is a nostalgic tale of the unexpected: Wonder Stories shows a family sitting down to dinner, with one of the diners slumped across an all-too-familiar cheesecloth covered table. The scene is both mysterious and intriguing: is the slumped diner dead, or is he simply objecting to the dish of the day?

All within a single room, the watercolours and magazines are beautifully complemented by the intimacy of the project space. Sebastián Gordín describes the process that led to making the magazines to be the result of improvisation and experimentation via his earlier stage-set series, comic book influences and watercolours.

Gordín does not paint or dye the wood himself, instead selecting already stained veneers. Choosing the wood is a critical task that Gordín undertakes himself, sourcing it from a distributer in Italy who acquires wood from around the world.

I like the idea of each veneer as a ‘found’ wood, already having a story of its own before seamlessly fitting into Gordín’s magazines, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Fantasy and irony are key themes that run through Gordín’s work, as does a deep vein of nostalgia. His drawings pay homage to Edward Gorey’s unsettling Victorian and Edwardian scenes, Winsor McCay’s comics from the turn of the century, the underground comic artists of the 60’s like Robert Crum and Spiegelman, as well as more contemporary comic artists like Chris Ware and Jim Woodring.

The sense of disquietude present in these artists’ work asserts itself in a particular way in Gordín’s magzines, leaving the viewer feeling as if they are standing on the edge of a precipice, waiting for something terrible to happen.

‘Terrible’ in Gordín’s visual language has the capacity to slip either way: manifesting as terribly beautiful and profound, or just plain terrible.

One suspects that for the goggly-eyed character that appears in many of Gordín’s magazines, the so-called terrible scenarios of death and disaster which linger like a long unspoken secret about to be revealed, are beautiful things: places of peace and transcendence from the whirligig of life.

Gordín has dubbed his character “the ghost” or “the time traveller.” This terminology is apt, as the raggedly dressed ghost seems to flit between the macabre and ironic situations of the present and the nostalgic past of childhood fantasy.

Irony, after all, is an adult response; it points to a lack of conviction at odds with childhood’s absolute belief in fantasy.

These thoughts are echoed in Gordín’s own writings on his magazines, explaining that he intends the magazines to evoke “a certain acuity we unlearn in life,” a rupture from our habit of “disciplining our senses and repressing our desires.”

Indeed, Gordín’s ghost, who appears to embrace his situations with something between bewilderment and curiosity, foresight and naivety, hints at life beyond the void, reminding us that it is not just the stuff of fantasy.