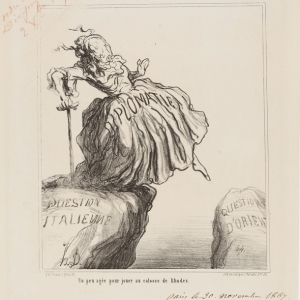

Not so Honoré Daumier (1808–79), whose career deftly combined the two, as demonstrated by ‘Visions of Paris’ at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (until 26 January 2014). Although his satirical cartoons, which made him famous, are undoubtedly humorous, their stealthy seriousness rescues his oeuvre from the oblivion of the pun. Added to this are Daumier’s profoundly serious paintings, which were hardly known during his lifetime, and the results are an artist who deserves to be considered alongside Manet and Degas in the pantheon of great 19th century figurative artists.

Daumier’s Ecce Homo (c.1849–52) is probably the masterpiece of this show. The Christ figure here is barely more than a shadow. But his form, so ingrained in the Western consciousness, can be conjured with a remarkable economy of means. Like a worn photocopy of the Mandylion, Christ here is an idea and not a specific man. The crowd on the other hand, although equally faceless, is a visceral entity. Full of fear, curiosity and hate, the viewer is placed within this throng. As such Daumier’s painting is more an examination of the dehumanising effects of the mob than a meditation on a specific religious doctrine.

Unlike his caricatures, which are necessarily imbued with a specific personality, Daumier’s painted figures are routinely anonymous. It is as if the process of exaggeration has reached its logical conclusion, and all that remains is the faint suggestion of a person. Where Daumier’s political art can be difficult to decipher, his painted subjects are recognisable types with generic back-stories.

Those back-stories are usually a tale of drudgery and woe. Such is his mastery of the medium, that all Daumier needs to communicate pathos are a few rapid marks. Whether painting or sketching, Daumier is essentially always drawing. Outline and matt swathes of colour dominate, creating presence without specific detail. Paradoxically, the results are at once both solid and fluid, rather like an unfinished clay sculpture. Daumier takes Michelangelo’s strapping angels and places them directly in the gutter.

His approach is typified by a series of works, known collectively as The Burden (1850–60). They depict impoverished women charged with two loads: a child and a bundle of laundry. In the context of this exhibition, the heartless men Daumier parodied in the newspapers are portrayed as the abandoners of these hunchbacked and subjugated ‘dependents’. This exhibition thus confirms our Dickensian fantasies by contrasting abject poverty and disaffection with laughable and corrupt statesmen.

Judging by this display, Daumier was an incurable pessimist. He dwells on the extremities of human emotion. One of his most enduring motifs is the dramatic gesture. The thrust of a pleading hand or the point of an accusative finger pervades this exhibition. In many of his works, such as The Strong Man (c. 1865–67), Daumier’s passive subjects are judged by an active intercessor.

The audience therefore perceives the subject through a third party. No longer innocent bystanders, we are made to feel complicit in the scene. We cannot, or possibly do not, intervene. This demoralising approach was perhaps atonement for Daumier’s own day job as a finger pointer. Indeed, arguably his corpus of paintings represents a fully realised counterpoint to his caricatures. The inherent irony and cynicism of his satire is juxtaposed with the plaintive sincerity of his paintings. As such, this exhibition creates a sense that Daumier’s career was essentially a grand experiment, one in which each facet of his art was an attempt to decipher another element of the human condition.