The Grand Palais’s enormous retrospective of Georges Braque seems determined to bring public attention to an artist sometimes unfairly referred to as the third man of 20th-century art, behind better-known masters Matisse and Picasso. Certainly less famous than his Spanish contemporary, Braque worked nonetheless hand in hand with Picasso to invent Cubism and to pioneer a revolution in the aesthetics of modern art.

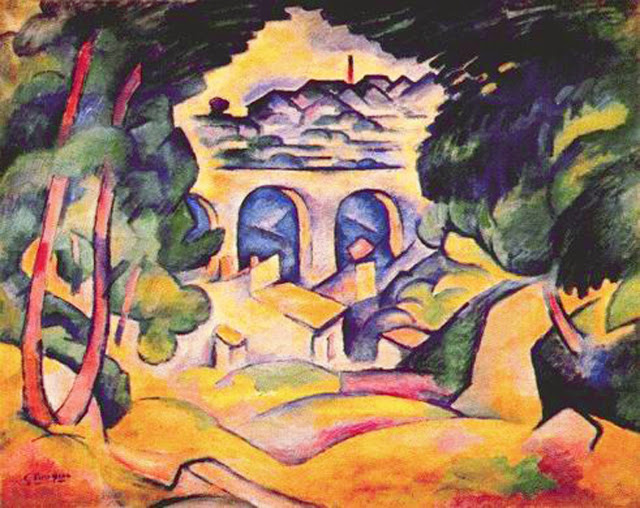

With almost 300 artworks displayed, the exhibition leaves virtually no period of Braque’s artistic career unexplored. The first gallery is dedicated to his early Fauvist nudes and landscapes, with the denatured colours and compositions of paintings such as Landscape at l’Estaque (1907), signalling an artist on the cusp of revolutionising his style. Sure enough, the second gallery opens with Large Nude (1907-08), arguably Braque’s most famous painting, and Houses at l’Estaque (1908), two of Cubism’s founding artworks and among the first to feature the movement’s characteristic presentation of multiple perspectives on a single flat surface.

The exhibition does an excellent job of exploring how Braque returned to the idea of simultaneous perspective throughout his career, with tremendously varied results. The muddy colours and blocky, impenetrable composition of Sacré Cœur (1909-10), pushes right at the limits of figuration and abstraction, whilst Violin and Pitcher (1909-10), and The Billiard Table (1947-49), demonstrate the spectacular force of the Cubist aesthetic, with solid objects seeming to shatter dramatically and pieces of furniture appearing to crumble under their own weight. Even when Braque seems to eschew the Cubist aesthetic, in more sensual paintings like The Canephors (1922), or The Three Bathers (1923-24), he remains preoccupied with stylised, exaggerated forms.

Introducing collage into the world of high art with pieces such as Still Life with Tenora (1913), Braque layered fragments of found paper, charcoal drawing and paint to create some of the first ever art that explicitly treated the canvas as a two-dimensional surface rather than as a painted illusion or representation, effectively opening the door to collage artists such as Kurt Schwitters and the synthetic Pop Art of the mid-20th century. Braque’s flat perspective paintings are his most touching, with the poignant simplicity of The Black Fish (1942), reflecting the melancholy of the second world war, and Black Bird, White Bird (1960), one of Braque’s final works, capturing a joyful sense of lightness and freedom.

With this expansive retrospective, the Grand Palais offers a reminder of Braque’s status as one of the leaders of the Cubist movement, and demonstrates without a doubt the artist’s considerable contribution to modern art. The fact that Braque has not had a similarly large retrospective since 1973 is an injustice that the Grand Palais has evidently resolved to remedy with much gusto.