Bleak, grey and morbid; these are words commonly used to describe 20th Century industrial England, and yet Lowry’s paintings of North West England’s urban landscape are attractive. The first major exhibition of his work by the Tate Britain, L.S. Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life, takes the viewer into the mind of a painter who sought to capture the industrial scene by which he was so affected.

The title, The Painting of Modern Life, summarises this artist’s work perfectly. One of his early paintings included in the exhibition portrays a black building with smoke pouring from the chimneys, and carries the frank title A Northern Hospital (1926), offering the viewer a very human insight into Lowry’s world. The painter, who notoriously hated sentiment, was not afraid to show life in Greater Manchester exactly as he saw it; from the hardships of the industrial 1920’s and 30’s to the political and cultural changes of the post-Second World War era.

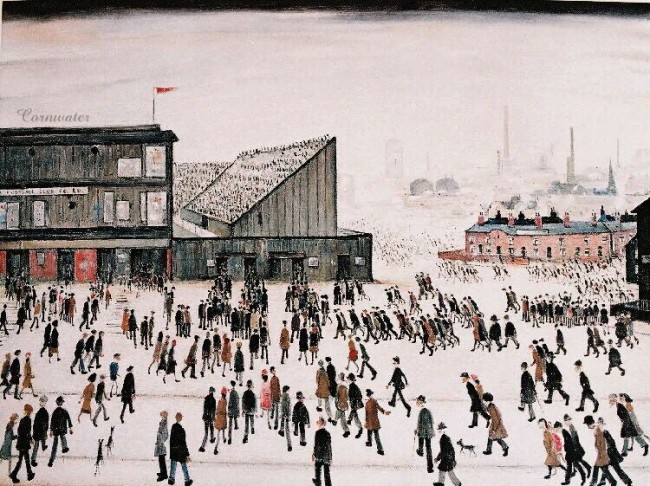

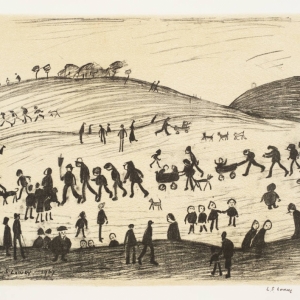

Distinctive figures inhabit Lowry’s paintings through the decades, making his style instantly unique and recognisable: his matchstick-like figures dash past red brick terraced houses, oppressive factory gates and blackened churches in swarms. There is perhaps a subtle satire in his depiction of modern street life. Whether his figures are ‘Going to Work’ or ‘Going to the Match’, they march in the same stoic way. The striking similarities in their postures and actions express the monotonous daily routine of the masses.

What is perhaps most touching about his work is the lack of drama with which he presents potentially heart-breaking scenes. In a collection which the Tate Britain labels ‘Street Life: Incident and Accident’, Lowry presents scenes of eviction and fever vans collecting sick children. In these subtle depictions, the focus is not on the dramatic events themselves, but the scenes surrounding them. Tragedy is almost overshadowed by daily life, which continues in the foreground, and in this way Lowry’s paintings are painfully truthful to real life.

The Tate Britain brings the viewer further into Lowry’s working class world by interspersing quotes throughout the exhibition. They include snippets of a contemporary song about the hardships of life, and commentary from social critics, such as George Orwell and Robert Roberts. In particular, a passage from Orwell’s ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’ brings to life Lowry’s painting Industrial Landscape (1955), both portraying slag heaps and factory chimneys. A real sense of history is created through the combination of art and literature.

Having spent the last year studying in Manchester, I found it fascinating to consider how the once industrial city has changed. Lowry’s work undoubtedly brought moments of nostalgia, with the hustle and bustle of crowds rushing past red-brick terraced houses and blackened churches. However, I cannot help but feel were Lowry alive today, his paintings of North West England’s landscape would take quite a different tone. The steady, grey, industrial city landscape has been softened with gentrified architecture, and the figures which pass through it are animated by a hub of music, culture and business.

Lowry was not the first or the last artist to be inspired by the industrial North. Their work serves as an ever important reminder of the history of Britain and its development in the modern world.